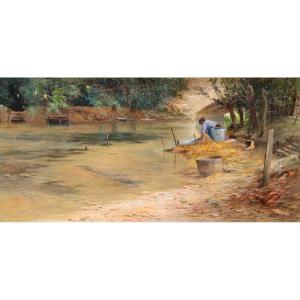

oil on canvas, 61.5 cm x 76 cm.

(Good overall condition despite some minor repainting and retouching)

19th-century carved and gilded wooden frame (damage and losses).

In the 17th century, Leiden was one of the most important and prosperous cities in the Netherlands.

It boasted an intense cultural life, imbued with humanism, with a university (founded as early as 1575) and a widely recognized school of painting frequented by great names such as Gerard Dou, Pieter Potter, and Harmen van Steenwyck.

All these painters were pupils of Rembrandt or strongly influenced by his work.

The "fijnschilders," the fine painters, as they were known, brought renown to the city.

Painting then underwent a form of democratization, even commercialization : alongside the masterpieces of the great masters, more modest works from workshops or less renowned painters circulated.

The subjects of their works were very varied: intimate interior scenes, boisterous scenes of peasant life, still lifes, or vanitas paintings… This genre, which influenced European taste, found its origins in the Protestantism that permeated Dutch society at the time. Indeed, the Protestant religion forbade all religious representation. Considering the major role of ecclesiastical patronage in Catholic countries at that time, where painting served as a veritable instrument in the service of faith and power, it is understandable that Dutch painters had to turn to other sources of inspiration, catering to a bourgeois clientele receptive to everyday subjects and more prosaic themes inspired by popular literature such as emblem books, and creating compositions laden with a whole repertoire of symbols.

The paintings are often small or medium-sized, the subjects bathed in soft light, creating an intimate atmosphere.

They are executed with great attention to detail: the rendering of fabrics, glass, and metals is extremely meticulous and realistic. Clothing, bodies, and symbols are painted with precision.

The further the viewer's gaze moves away from the subjects and attributes, the more imprecise and light the brushstrokes become, and the darker and more blurred the scene appears.

Dogs, a bed, a set table, a musical instrument... these motifs appear in many works.

The English particularly appreciated this artistic genre and reserved a place of honor for these paintings in their homes*.

In the foreground, a young woman and a gentleman are seated.

They are richly dressed : she, adorned with pearls, he, wearing a sword and a chain with a medallion. The room features an imposing fireplace, and the furniture consists of fine fabrics and highly ornate pieces. Both undoubtedly come from established families. The man's gestures define the emotional and physical charge of the scene : he is assertive. The young woman appears modest, troubled, and reserved. The dog, lying close to her, is in a way the guarantor of her virtue. On the floor, a rose. This flower has multiple meanings: pale in color, it is associated with gentleness and tenderness, but also with romance, beauty, and femininity. On the left, a lute is leaning, presumably against a seat upon which rests a garment. An open window reveals a view of a park or wood; a bouquet of flowers sits on the sill, and a drawn red curtain lets in soft light. On the set table lie a plate, a platter with a cut melon, a half-peeled lemon, a ewer, and a glass of wine—a collection of small still lifes typical of Dutch works of this period. In the dim light, a four-poster bed with a canopy adorned with valances and a headboard sculpted with strange beings appears unmade. Another dog lies on this bed. The explanation for these symbols may lie in Otto Van Veen's "Emblem Book," a collection of love emblems illustrating human passions. This scene can thus be interpreted as representing the different stages of the duality of soul and body, a relationship where the line between good and evil, morality and self-fulfillment, is razor-thin : the young woman's restraint contrasting with the gentleman's ardor; flowers and their perfumes associated with seduction, used to lead astray innocence; sweet words replacing the pure musical notes evoked by the lute; the meal, a carnal symbol, contrasting with Christian morality symbolized by wine; all of this juxtaposed in the dim light with an unmade bed and diabolical symbols.

But let us not be misled by the appearances of this moment, even if it contributes to the main subject of our painting : the various elements brought together in this work are also an evocation of the five senses. Sight is symbolized by the gazes of the two lovers, touch by the hands placed on the young woman's shoulder and wrist, hearing by the lute casually resting against a cloth-covered seat, smell by the bouquet of flowers and their fragrance, and finally taste by the meal placed and partially eaten on the table. Lastly, the peeled lemon, a recurring motif in Flemish and Dutch still lifes, symbolizes the unfolding of earthly life and the gradual shedding of the physical body to liberate the soul and spirit.

"Attempting to reconstruct the meaning of Dutch genre painting is a true exercise in cultural anthropology and can prove more delicate than reconstructing, for example, Rubens' literary influences," in "Dutch Genre Painting in the 17th Century," Christopher Brown, curator at the National Gallery, London.

Typical of the Leiden school, and like the majority of works produced there, our painting is unsigned. However, one can recognize the type of composition and the characteristics of the works of Dirk Druyf (Leiden 1620-1669), to whom it is attributed (we issue a certificate for this attribution).

(S.D. / E.J.)

* In this regard, an inscription and a label affixed to the back of the stretcher indicate a British provenance: the painting was part of Mr. Ficher's collection and was stored in a furniture warehouse in Jersey.

Le Magazine de PROANTIC

Le Magazine de PROANTIC TRÉSORS Magazine

TRÉSORS Magazine Rivista Artiquariato

Rivista Artiquariato