Francesco Laurana (1430-1502) - Marble Bust Depicting the Portrait of an Aragonese Youth.

The journey of Francesco Laurana, the celebrated Dalmatian sculptor born in present-day Vrana (Aurana) near Zadar—a Dalmatian village under Venetian rule in the fifteenth century—is one of rare fascination and cultural complexity. This journey is further attested by this previously unrecorded and captivating bust of a youth (figs. 1-4). Characterized by rounded volumes and essential features sculpted with particular lightness and a marked abstract intent, these stylistic traits are indeed peculiar to the sculptor. Laurana, especially in his female portraits carved during his second Neapolitan sojourn—the most fertile period of his portraiture career—managed to combine elements that resonate with the formal synthesis found in the works of Antonello da Messina and Piero della Francesca, particularly in his busts depicting Aragonese princesses.

It was precisely his portraiture that defined the sculptor's practice, giving him a significant role in the dissemination of Renaissance figurative culture, as evidenced by his biographical trajectory: active from the mid-fifteenth century at the Aragonese court in Naples, he is first documented there in 1453 as "Francisco da Zara," receiving payment with other masters for work on the Triumphal Arch of Castelnuovo. Subsequently, in 1466, he arrived in Provence, serving René d'Anjou. After a second Neapolitan sojourn, he was active in Sicily and then again at the Aragonese court until he settled in Marseille and Avignon, where he died.

Portrait busts, typically cut just below the shoulders, like the example examined here, represent a significant genre of the Florentine Quattrocento. The sculptors who most contributed to its development were Donatello, Mino da Fiesole, Desiderio da Settignano, Antonio Rossellino, and Benedetto da Maiano. Their function was to legitimize the nobility of the time, and for this reason, such works were primarily commissioned by aristocratic families and the upper mercantile bourgeoisie. In Florence, the city from which this genre spread to other Italian courts, its rediscovery by these artists was underpinned by the revival of classical culture promoted by humanists, the re-evaluation of human individuality, and the study of Roman busts placed in the domus to commemorate the virtues of deceased family members. For these reasons, these works highlight extreme realism in physiognomy and acute psychological introspection. Examples include the painted terracotta bust of the humanist Niccolò da Uzzano at the Museo Nazionale del Bargello in Florence, formerly attributed to Donatello and now considered by Desiderio da Settignano; the portrait of Piero de’ Medici (1453) sculpted by Mino da Fiesole, also at the Bargello; that of the physician Giovanni Chellini (1456) by Antonio Rossellino at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London; and the Florentine merchant Pietro Mellini, an ally of the Medici, executed by Benedetto da Maiano, also at the Bargello.

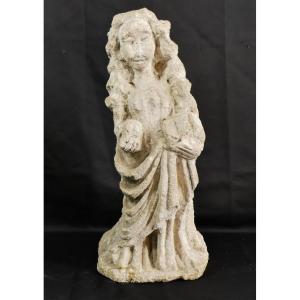

Analysis of Laurana's Bust and its UniquenessIt is within this figurative culture that our bust (figs. 1-4) must be discussed to appreciate its qualities. It likely depicts a young man from the Aragonese court, fashionably and elegantly dressed in a velvet tunic with wide lapels finished by a collar. The bust is in good condition, although the marble surface appears somewhat eroded in certain areas.

The young man's oval, tender, gentle, and noble face, with its rarefied expression, is characterized by essential features, smooth, rounded forms, and eyebrows from which fixed eyes convey an almost imperturbable expressiveness. The finely trimmed eyelids lend the gaze an expression of powerful introspection. His voluminous, elegant, and flowing hair, distinguished on the domed forehead by a prominent forelock, falls just above the shoulders, creating the impression of a soft cap, even in profile views (figs. 2,3). The accurate depiction of the subject, capturing both his character and his attire—such as the soft, fluted velvet giornea that highlights his slender and still delicate body structure, with the drapery folds standing out with calibrated precision—suggests it is a portrait of a member of the Aragonese court or the Neapolitan aristocracy.

Observing our youth, we can also understand Laurana's role in the development of the portrait bust genre during the Quattrocento. The Dalmatian sculptor, while adopting the typology developed by Florentine sculptors, positions himself at the antipodes of Donatello's naturalism, rendering the subject's features through a pronounced hieratic idealization of forms. This is evident in this work through the almost abstract purity of the face, the volumes with a solid compositional structure (observe the profile views as well: figs. 3,4) that appear frozen in their geometric purity. These peculiarities, combined with an attention to costume details derived from contemporary fashion (the style of the garment and hairstyle), qualify Laurana's portraiture through two contrasting aspects which, in their combination, encapsulate the charm of such works.

This uniqueness was likely instrumental in the success of Laurana's portraiture at Italian and European courts during the Quattrocento. A crucial role in the development of this expressive specificity was played by the lively artistic environment of the Neapolitan court, where stylistic elements from Lombard sculpture, Franco-Flemish painting, and Florentine art converged due to the presence of artists from all over Italy, becoming influential models in contemporary Italian portraiture. Thus, in our youth, a marked degree of realism (resemblance to the sitter), achieved through careful modeling of surfaces with a preference for soft forms (as seen in the mouth with its fleshy and pronounced lips) and a solid, proportionate volumetric structure derived from Roman portraiture, is fused, in a rigorously frontal portrait bust, with a strong tendency towards idealization. This idealization is expressed in the rendering of introspective features (note the carving of the eyes) with an incisive clarity that Laurana consistently achieves in his marble works.

Attributions and Shared Artistic TraitsThe common figurative koinè to which certain sculptors active in Southern Italy belonged, such as Laurana and the Lombard Domenico Gagini, has led critics to discrepancies regarding the catalogue of these artists, which has often intertwined, attributing certain works alternately to one or the other. However, it is possible to establish appropriate comparisons between our bust and other marble portraits attributed to the sculptor.

A bust of a boy at the Musée Calvet in Avignon (fig. 7), with soft and regular features and very finely cut eyes, is consistently attributed to Laurana by critics. A half-bust of Saint Quirico (fig. 6) at the Paul Getty Museum in Malibu has recently been attributed to Laurana. A bust of a young man (fig. 9) at the Galleria Nazionale in Palermo is debated between our sculptor and Domenico Gagini; a similar situation has involved a bust of a youth (fig. 11) at the Ca' d'Oro in Venice, possibly depicting Federico Gonzaga, attributed by Middeldorf to Laurana and recently to Gian Cristoforo Romano. With these works, our bust shares the calm turning of the image, the plastic and firm volumetric rendering, the oval setting of the face, and the polish and extreme delicacy of the features, which lean towards formal abstraction.

Laurana was again present in Naples in the early 1480s. It is to this chronological period that we propose to attribute our bust, sophisticated in its degree of formal refinement, where traces of his vast figurative experience converge. It is a work in which we identify that modern expressive sensibility, balanced between individual characterization and abstraction, which constitutes the peculiar quality of Laurana's portraiture.

Le Magazine de PROANTIC

Le Magazine de PROANTIC TRÉSORS Magazine

TRÉSORS Magazine Rivista Artiquariato

Rivista Artiquariato