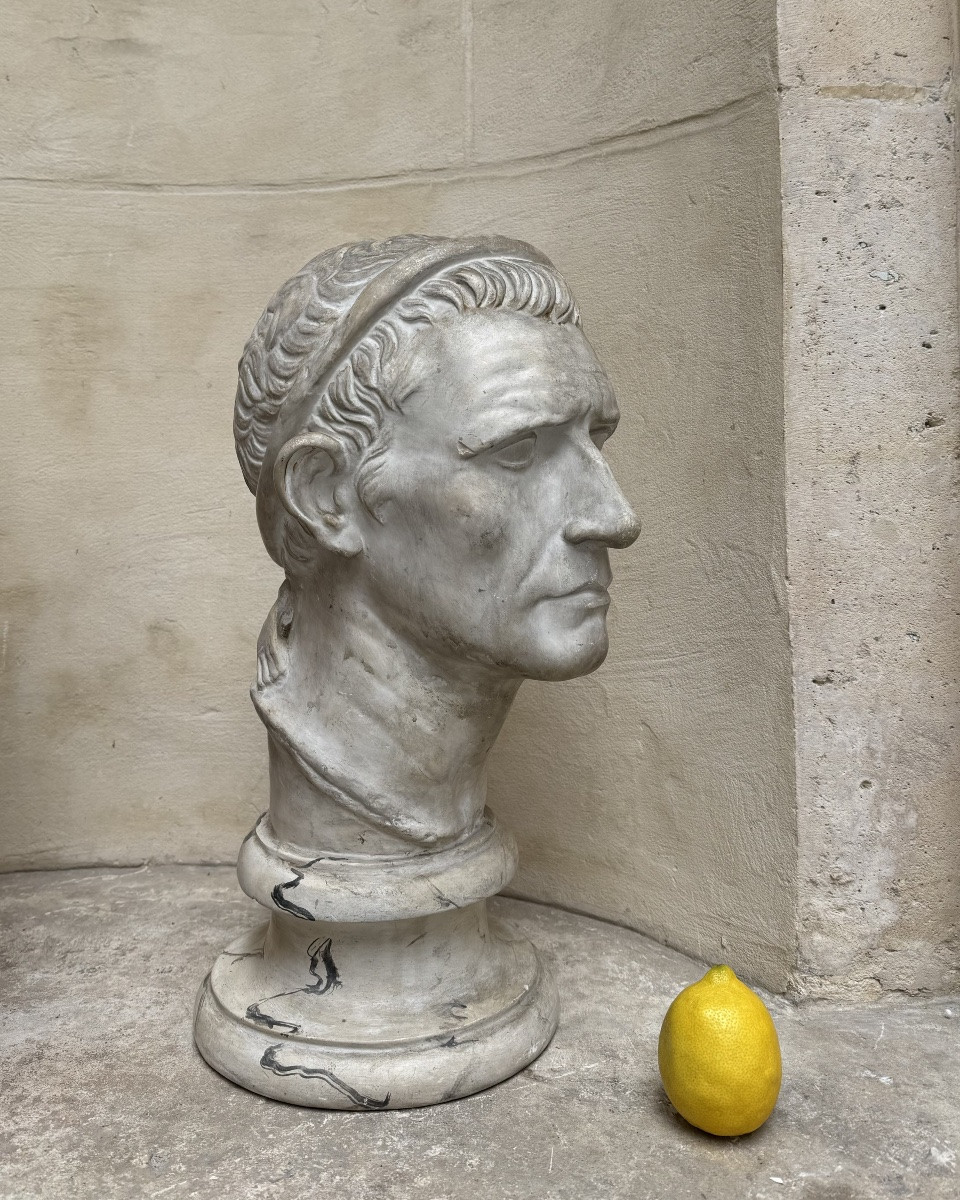

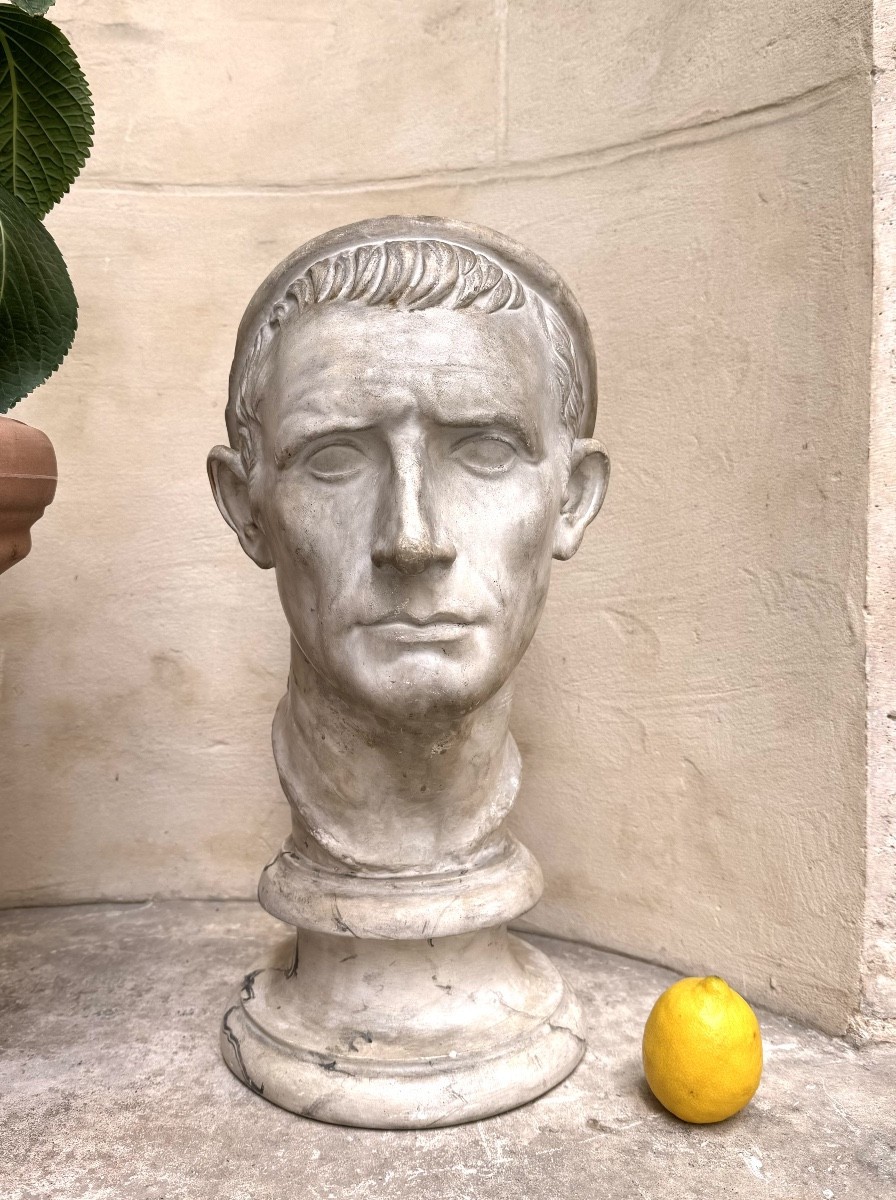

Plaster bust representing Antiochus III, known as Antiochus the Great, after the Hellenistic original kept at the Louvre Museum (inv. MA 3227). This antique cast is made of hollow plaster with a beautiful patina imitating marble, and rests on a molded pedestal painted in imitation of marble. At the back, the hair is held in place by a knotted headband.

Under the base, an original metal disc bears the inscription “Musée du Louvre – Reproduction interdite – Atelier de moule”, typical of the productions made by the museum workshops between 1905 and 1928, before the creation of the Réunion des Musées Nationaux.

Very good general condition. Traces of use, superficial soiling. No visible restoration.

Seleucid king Antiochus III reigned from 223 to 187 BC over a vast empire spanning Western Asia. Ambitious, he undertook to restore the grandeur of the kingdom founded by one of Alexander the Great's generals. He reconquered Media, Persia, Babylon, and even Armenia. His confrontation with Rome, marked by the defeat at Magnesia in 190 BC, signaled the decline of his power. However, he remains one of the most influential rulers of the Hellenistic period.

The original model for this cast is a Hellenistic marble bust, preserved in the Louvre Museum. It represents Antiochus III, sovereign of the Seleucid dynasty, identifiable in particular by his idealized features, his noble bearing and the headband (diadem) tied around his hair – a characteristic attribute of Hellenistic kings, symbolizing their dynastic power. Found in Asia Minor or Syria, it could come from a dynastic or honorary context (sanctuary, royal palace, gymnasium). The work is emblematic of the Hellenistic royal portrait, which mixes a certain idealization inherited from Alexander the Great (calm, balance, formal beauty) with a desire for political typicality (recognition of power through attributes such as the diadem). The face is grave, the features clear, the forehead high and the eyes deep: the expression conveys authority, firmness and rationality – the qualities expected of a sovereign. This portrait is one of the few preserved of an identified Seleucid king. It participates in this tradition of representing sovereigns as legitimate heirs to the power of Alexander and testifies to the diffusion of Greek art in the eastern provinces during the Hellenistic period.

Le Magazine de PROANTIC

Le Magazine de PROANTIC TRÉSORS Magazine

TRÉSORS Magazine Rivista Artiquariato

Rivista Artiquariato