The movement needs to be restored, the pendulum and bell are missing.

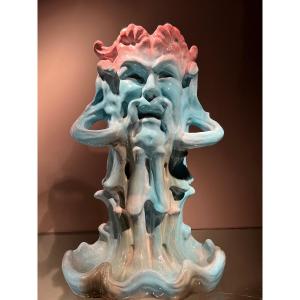

This ruin-clock is a perfect example of the Romantic aesthetic applied to the decorative arts: it unites poetry, history, ruins and the mechanism of time in a single object. Both a visual meditation and a functional object, it illustrates the 19th century fascination with the monumental and perishable past, transformed here into a domestic sculpture.

Ruins in painting and sculpture in the 19th century:

In the 19th century, ruins occupied a central place in the artistic imagination. They became much more than a simple decoration: they were the mirror of a changing world, a symbol of the passing of time, of memory, and often of human finitude. Heirs to an interest already strong in the Age of Enlightenment, ruins continued a tradition that was at once philosophical, aesthetic and political in the 19th century. Romantic art made them a favored motif. For painters like Caspar David Friedrich, Gothic or ancient ruins, invaded by mist and nature, become interior landscapes, reflecting human solitude in the face of eternity. They are no longer simply witnesses to a glorious past, but objects of melancholic meditation. The gaze directed at them is imbued with nostalgia, sometimes despair, often with a feeling of the sublime, as Edmund Burke defined it: a beauty mixed with vertigo, grandeur, and loss. Other artists, like Hubert Robert, already active at the end of the 18th century, built an entire body of work around ruins—sometimes real, sometimes imaginary. These decaying landscapes become poetic visions, where man seems minuscule in the face of the work of time. Turner, for his part, sometimes envelops ruins in storms of light and elements, giving them an almost cosmic dramatic power.

In gardens and architecture, the fashion for “factories” extends this craze: false ruins are erected to arouse emotion, to represent the ephemeral. These artificial constructions become picturesque symbols, inviting reverie and contemplation.

Sculpture, although less focused on this theme, is not left behind. We find fragments, broken statues, collapsed columns that recall the vestiges of the past. These elements, integrated into larger compositions, reinforce the feeling of loss and vanished grandeur. Ruins also take on a political dimension. After the upheavals of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, they symbolize the collapse of empires, the vanity of powers, but also the idea of starting over. They fuel emerging nationalist discourses: in Germany, for example, medieval ruins become emblems of an identity under construction.

Finally, some artists go even further, inventing visionary or futuristic ruins, like Piranesi, whose “carceres” are rediscovered with fascination. These imaginary ruins open a new path: that of a world in ruins before it even existed. A form of artistic pre-science fiction, which already questions the future of our civilization. Thus, ruins in the 19th century are not just a vestige of the past: they become the language of an era in search of meaning, a universal symbol of human fragility, a playground for the imagination and a support for reflection on history, memory and the destiny of peoples.

Le Magazine de PROANTIC

Le Magazine de PROANTIC TRÉSORS Magazine

TRÉSORS Magazine Rivista Artiquariato

Rivista Artiquariato