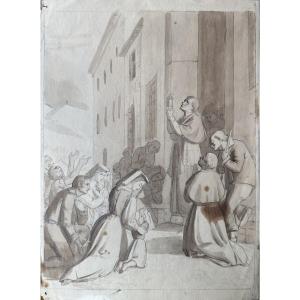

SAINT CHARLES BORROMEO LEADING A PUBLIC EUCHARISTIC DEVOTION

GIACINTO MASSOLA

Sarzana, 1820 – Genoa, 1865

Pencil and grey wash on paper

29 × 22 cm / 11.4 × 8.7 in

With margins: 31.5 × 24 cm / 12.4 × 9.4 in

Unframed

This drawing depicts Saint Charles Borromeo leading a public Eucharistic devotion — a subject deeply rooted in the religious and social history of Lombardy, where Borromeo was venerated not only as a saint, but as a moral and civic figure of exceptional importance.

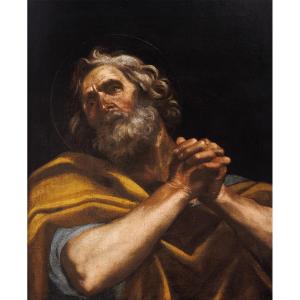

Charles Borromeo (1538–1584), Archbishop of Milan and one of the central figures of the Catholic Reformation, embodied a new ideal of the Christian pastor. A cardinal, reformer, and man of profound personal austerity, he devoted his life to pastoral care, education, and direct engagement with the faithful. During times of crisis — most notably the plague in Milan — he was known to walk the streets in poverty, nursing the sick and selling his own possessions to support the poor. His figure came to symbolize a Church that was present in daily life, attentive to suffering, and grounded in moral responsibility.

In this drawing, Massola presents Borromeo not as a distant hieratic figure, but as an active spiritual leader, surrounded by the people. The composition emphasizes gesture, posture, and collective movement rather than theatrical drama. Faith here is shown as a shared, public act — quiet, disciplined, and deeply communal.

The work belongs to Massola’s mature period and reflects the concerns that define his art: religious history, ethical responsibility, and the emotional life of the past. A painter from Liguria trained at the Accademia Ligustica in Genoa, Massola combined academic discipline with a growing sensitivity to Romantic themes, particularly in subjects drawn from Christianity and Dante. His work often bridges personal devotion and historical reflection.

At the same time, this drawing is of particular interest as part of Massola’s pedagogical practice. It was most likely executed as a teaching model for his students. The reverse of the sheet shows traces of graphite rubbing, and the figures on the front bear pressure marks — evidence of an old academic method in which students copied a master’s drawing by transferring its outlines through the paper. In this sense, the work functions both as an autonomous composition and as a witness to nineteenth-century artistic training.

Le Magazine de PROANTIC

Le Magazine de PROANTIC TRÉSORS Magazine

TRÉSORS Magazine Rivista Artiquariato

Rivista Artiquariato