Circle of John Michael Wright (1617-94)

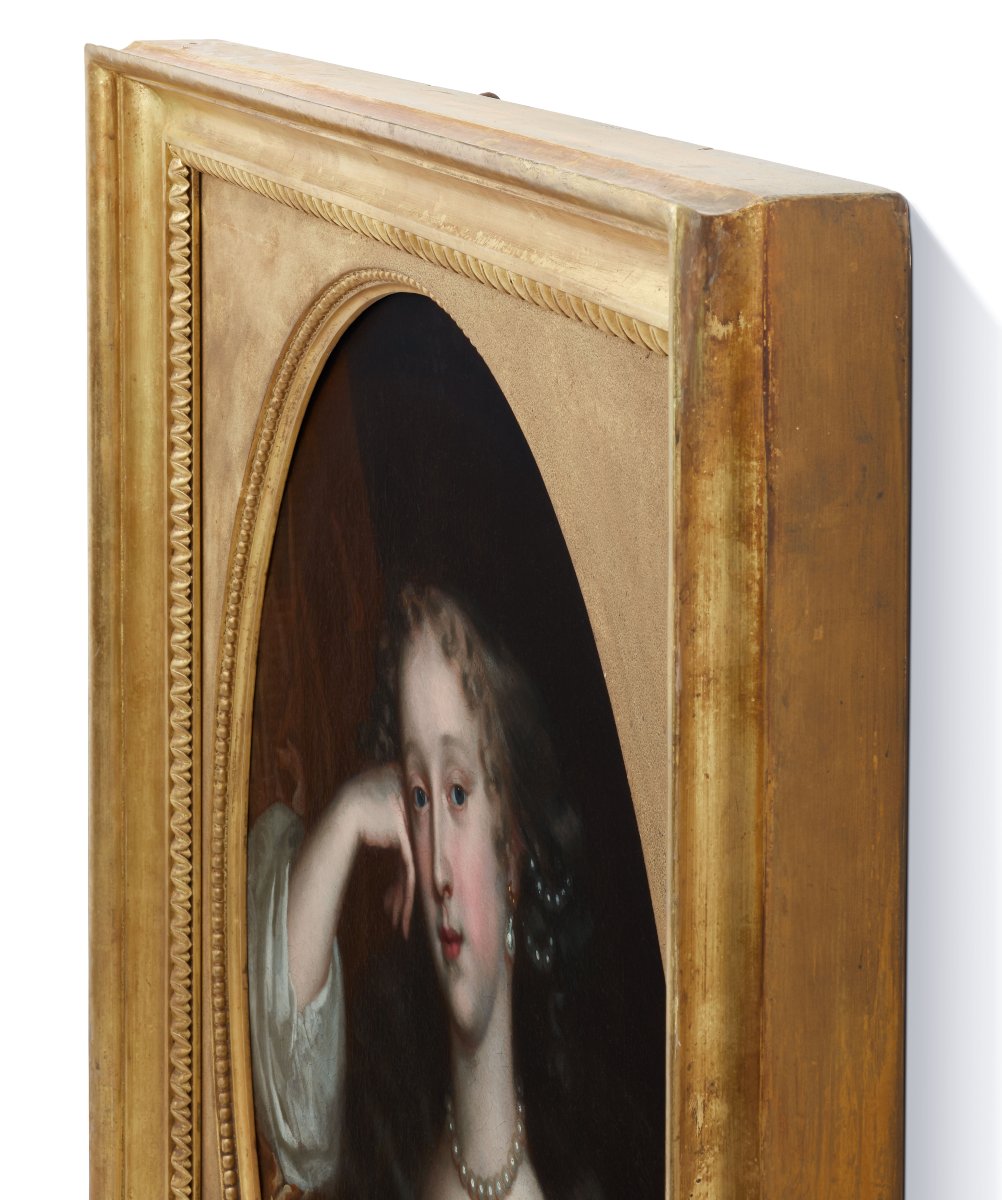

In this touching composition, painted around the time of London’s Great Fire in 1666, a young woman has been depicted wearing a silver dress and gauzy scarf held in a place by a rope of pearls and a large diamond brooch. At first, the image seems like a straightforward one, but it in fact it carries aesthetic and allegorical illusions, and their meaning would have been immediately recognised by a contemporary audience.

The subject is said to be Elizabeth, daughter and co-heir of Charles Nodes of Shephalbury, Hertfordshire. She was born on 1 August 1648. She married Charles Fane, 3rd Earl of Westmorland (1635-1691), in 1665, the year he succeeded to the Earldom; she then became styled as Countess of Westmorland. The family seat was Apethorpe Hall.

Charles was the eldest son of Mildmay Fane, 2nd Earl of Westmorland and his first wife Grace Thornhurst. He was an English peer and twice Member of Parliament for Peterborough. When his father died on 12 February 1666, he inherited the earldom of Westmorland, as well as his father's further titles Baron Burghersh and Baron le Despencer. Though apparently an opponent of James II in 1684, he refused to take up arms against the King the year after. He died at the age of 56 and was buried at Apethorpe Hall.

She died sometime after 1667, with some records indicating the year 1667.

The ‘head on hand’ pose was long depicted in art and has its origins in the Renaissance depictions of beautiful women, particularly those of Titian and his followers, and also the iconography associated with the depiction of Melancholia, the Penitent Magdalene. In England, however, the prolific painter Peter Lely, popularised this formula, due to his widely celebrated depiction of Barbara Villiers (circa 1662). The Restoration court was a reaction against the austere Puritanical period that preceded it. Lely's paintings, with their relaxed and sensual poses and unbound hair, reflected this new, more indulgent atmosphere. Lely used it often and many other artists followed; it became a pose very much associated with a young beauty of the day.

The flowing hair holds several meanings associated with the Restoration era: it was a symbol of uninhibited sexuality, unlike respectable married women of the time who kept their hair neatly pinned up. Having one's hair loose and unbound was a highly intimate and provocative gesture as "virtuous" women only let their hair down in the privacy of their bedchambers. It was sometimes depicted in allegorical roles, such as the Roman goddess Minerva, placing her in the context of mythical figures who often had unbound, flowing locks. However, our portrait, considering the contemplative pose, and the fact that Wright is known to have painted a posthumous portrait of the sitter (*), can be considered as a memento mori, a reminder of mortality and the impermanence of beauty.

The work is a fine example of English Baroque portraiture and it illustrates exceptional skill, and an individualised face. Held in a period gilded antique frame with sanded spandrel.

John Michael Wright was one of only a handful of native-born painters to find favour amongst the top echelons of society. He introduced an Italian flavour into British painting, unlike all the other portrait painters in second half of the century. His realistic characterisations tend to reinforce Pepy’s critique that Lely’s portraits were ‘good but not like’ and, in 1662, when comparing the two artists “but Lord, the difference that is between their two works’.

He was born in London and initially trained in Edinburgh under the apprenticeship of George Jamesone, a painter of notable repute whose work was comparable to that of his English contemporaries in London. In the early 1640s, he went to Rome, and immersed himself in the study of some of the most distinguished painters of the time. By 1648, he had become a member of the Academy of St Luke, joining the ranks of other prominent artists such as Poussin and Velasquez. He returned to London in 1656, and two years later, a publication recognised him as one of the foremost artists in England.

Wright's distinctive individuality and success as an artist can be attributed, in part, to his varied artistic background and training. Over the course of more than a decade spent in Rome, along with his painting practice in France and presumably the Netherlands, Wright amassed a breadth of experience that surpassed that of any other painter in Britain during the latter half of the 17th century. This extensive experience lends an international quality to his works. Most of his subjects do not conform to any prevailing facial archetype; instead, they possess features that are uniquely and skilfully individualised, contrasting sharply with Lely's conventional portrayals of female beauty. Furthermore, Wright's colour palette, characterized by cooler and muted tones is quite different from Lely’s typically warmer hues. The women depicted in his portraits, who were primarily outside the courtly circles, embody a more traditional feminine demeanour marked by quiet and submissive modesty.

*Christies London, 17 Dec 2020, lot 246, as “A posthumous portrait of Elizabeth, Countess of Westmorland (1648-?1667), full-length, seated in a white satin dress with gold and silver brocade, with a sprig of flowers in her left hand, JOHN MICHAEL WRIGHT (LONDON 1617-1694), inscribed 'Eliz. th Nodes 1st. Wife / to Chas E. of Weftmorland' (lower left)

Measurements: Height 92cm, Width 79cm framed (Height 36.25”, Width 31” framed)

Le Magazine de PROANTIC

Le Magazine de PROANTIC TRÉSORS Magazine

TRÉSORS Magazine Rivista Artiquariato

Rivista Artiquariato