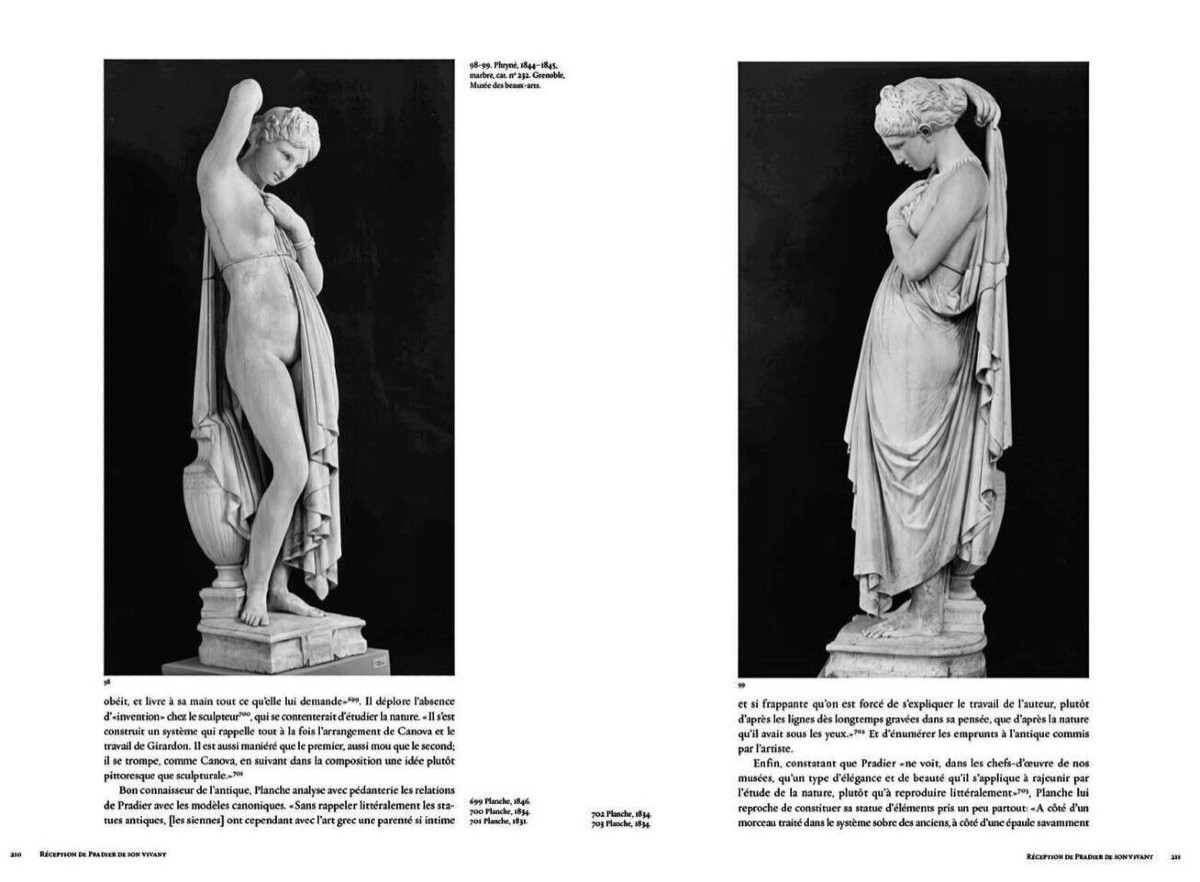

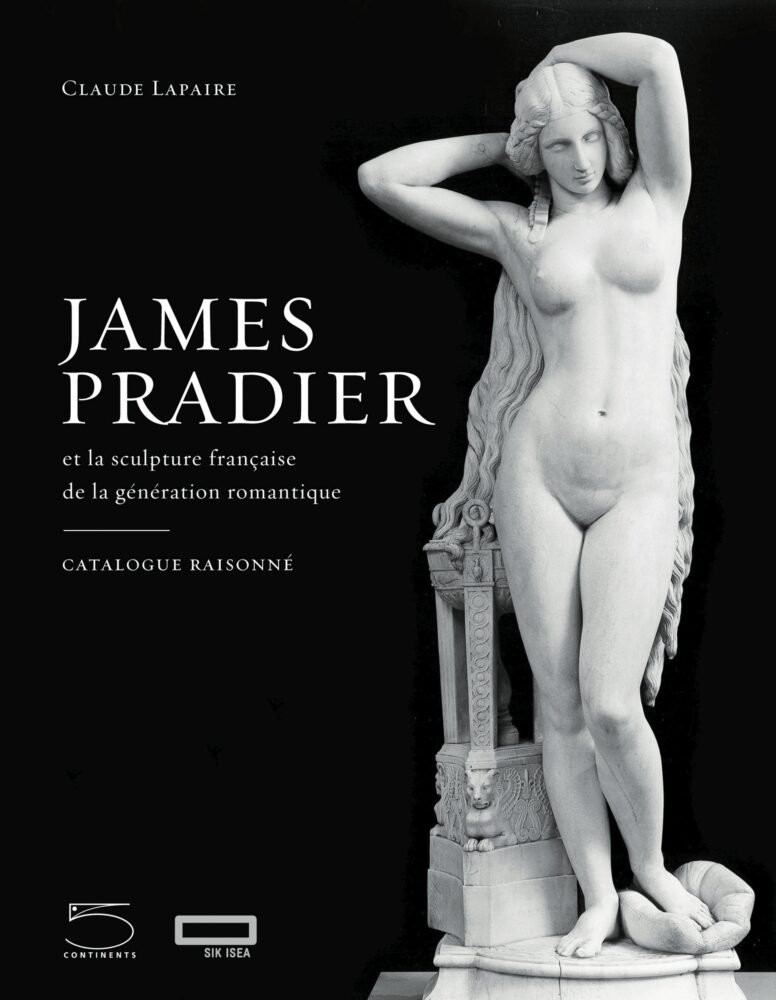

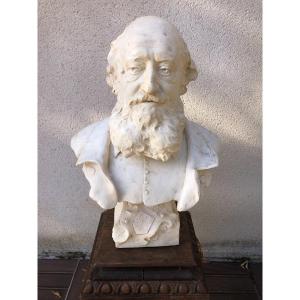

James Pradier belongs to a generation of sculptors from the first half of the 19th century who were influenced by Hellenism, and whose taste for the Antique was revived by the Greek models discovered during this period, such as the Venus de Milo or the Parthenon marbles. The collections of the Louvre, enriched by the Empire, were abundant sources of inspiration during training at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris where Pradier was a student of the sculptor Frédéric Lemot. In 1813, Pradier won the Prix de Rome and settled for five years in the eternal city. The success of his Bacchante at the 1819 Salon marked the beginning of a brilliant career and secured him numerous commissions. While Pradier's work is fully in keeping with the era of "Ideal Beauty" revived by the neoclassical movement, the sculptor inflected its austerity by giving the female nude, his favorite theme, accents that were sometimes romantic, sometimes realistic, elegant, or sensual. The first monumental representation of the subject, Phryne, was one of the most noted sculptures at the 1845 Salon. Having initially sketched a nymph figure, Pradier eventually gave her the name Phryne. A courtesan of Athens, Phryne was said to have been the model for Praxiteles, whose mistress she was. Accused of impiety, she was unveiled by the orator Hyperides before the judges of the Areopagus, who acquitted her because of her beauty. Pradier, who saw himself as a worthy heir to Praxiteles, sculpted her figure in Parian marble, which he enhanced with polychromy and gold, traces of which remain on the edge of the drapery. Inspired as much by the Greek sculptor's Diana of Gabii as by the nymphs of Goujon's Fountain of the Innocents or Ingres' Venus Anadyomène, Pradier achieves a subtle balance of volume and line, the tight folds of the drapery highlighting the fluid, ample forms of the female body. The suspended gesture, the inclination of the head, and the slight contrapposto lend Phryne a reserve and an internalized grace that instill doubt: is she veiling or unveiling herself? This element of mystery gives the figure a sensuality that blends with the aspirations of "noble simplicity and calm grandeur" advocated by Winckelmann.

Le Magazine de PROANTIC

Le Magazine de PROANTIC TRÉSORS Magazine

TRÉSORS Magazine Rivista Artiquariato

Rivista Artiquariato