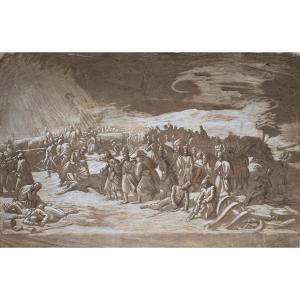

DIOGENES AND ALEXANDER

ITALIAN SCHOOL, second half of the 17th century

Pen and brown ink on laid paper, laid down on old mount

30 × 25.5 cm / 11.8 × 10 in

with mount: 34 × 27 cm / 13.4 × 10.6 in

Minor foxing and small traces of handling consistent with age; the sheet remains strong, the ink fresh and the hatching remarkably crisp.

PROVENANCE

– Private collection, France

Executed by an assured and highly competent hand, this finely worked pen drawing exemplifies the sophistication of a mature Italian draughtsman of the second half of the seventeenth century. Although the composition follows the engraving by Jacobus Rainus, after Pietro Liberi and published in Venice in 1672, the quality of execution reveals a master fully in command of his medium. The density and precision of the hatching, the firm anatomical modelling and the subtle transitions of tone elevate the sheet far beyond the level of a mechanical copy, transforming it into an autonomous interpretation informed by the print yet animated by an independent artistic intelligence.

Although Rainus’s engraving was itself based on a design by Pietro Liberi, renowned for his expressive colourism, the iconography of Diogenes confronted by the youthful Alexander resonates more strongly with the Venetian tradition of tenebroso cultivated by Antonio Ruschi, Antonio Zanchi and Antonio Maria Negri. The powerful anatomy of Diogenes in the foreground, emphatically modelled through densely woven hatching; the sharp, almost Caravaggesque light that accentuates his muscular form and introduces a discreet sensual presence; the dramatic interplay between the ascetic philosopher and the noble youth; and the richly material rendering of the drapery, conveyed through tight, saturated strokes that impart a painterly depth — all align the drawing with the visual language of the Venetian followers of Caravaggio.

The moral tension embedded in the scene — a confrontation between philosophical self-sufficiency and worldly authority — was particularly resonant in late seventeenth-century Venice, where moral subjects were often heightened through corporeal intensity and dramatic illumination. The anonymous draughtsman engages this tradition with notable authority: the figures emerge with a vivid, tactile immediacy, shaped by the fall of light rather than by contour alone.

Although the present drawing does not preserve the dedicatory inscriptions, the original engraving on which it depends carried a full dedication, offering valuable insight into the intended audience of the print and clarifying the intellectual framework behind Liberi’s invention. The text reads:

CAROLO IARCHAE, VIRO CLARISS.ᵐᵒ ET MEDICO CERTISS.ᵐᵒ

Hic hominem frustra quaerit; sed, CAROLE IARCHA,

Spirite tua foelix, tu mihi Numen ades.

Petrus Liberi invenit

Stefano Scolari formis

Jacobus Rainus sculpsit Venetijs 1672

Such dedications were characteristic of Venetian print culture in the period, often honouring distinguished scholars, physicians and patrons. In this instance, the dedication underscores the intellectual purpose of the original engraving and confirms Liberi as the author of the underlying invention.

Grounded in a celebrated graphic model yet executed with striking independence, the present sheet stands as a compelling example of seventeenth-century Italian draughtsmanship — a work that unites technical assurance, Venetian dramatic sensibility and a vivid reinterpretation of a philosophically charged subject.

Le Magazine de PROANTIC

Le Magazine de PROANTIC TRÉSORS Magazine

TRÉSORS Magazine Rivista Artiquariato

Rivista Artiquariato