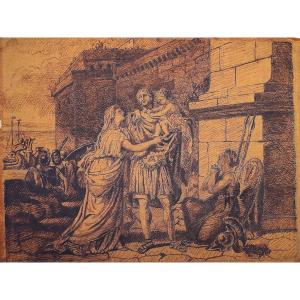

IMPERIAL ROMAN BATTLE SCENE

NEAPOLITAN SCHOOL, CIRCA 1760

Pen and brown ink with sepia wash on paper

25 × 30 cm / 9.8 × 11.8 inches, with antique frame 40.5 × 45 cm / 15.9 × 17.7 inches

PROVENANCE

Private collection, France

This highly animated drawing, executed in pen and brown ink with sepia wash, evokes the violence and movement of ancient warfare with striking theatricality. A whirlwind of rearing horses, lunging warriors, fallen bodies, and fluttering standards converges in a vortex of action, structured yet intentionally chaotic — a composition that recalls the great battle scenes of Antonio Tempesta or the later bravura of Luca Giordano.

Yet upon closer inspection, both the draftsmanship and material evidence point to a more recent date. The laid paper bears the watermark “La Briglia”, a well-known Tuscan papermill active from the 1750s onward, whose products were widely used by Italian artists throughout the second half of the eighteenth century. Despite the paper’s seemingly archaic texture, this watermark provides an unambiguous terminus post quem and becomes the key to dating the work accurately.

Stylistically, the drawing displays a deliberate archaizing tendency, in which the artist — likely trained before the full impact of neoclassical purism — revives the energy and compositional swirl of late Baroque battle imagery. The generalized treatment of forms, especially in the musculature and drapery, reflects a post-Giordanesque hand, possibly active in Naples around 1760, where theatrical grandeur and historical reverie continued to flourish.

Of particular iconographic interest are the Roman eagles (aquilae) borne atop the military standards. Their presence clearly places the scene within the symbolic universe of Imperial Rome, as the eagle became the defining emblem of the legions during and after the reign of Augustus. The precise episode remains elusive — the scene might refer to a battle from the campaigns of Caesar, Trajan, or simply stand as a heroic allegory of Roman might, as was fashionable in academic circles and antiquarian art of the time.

Rather than functioning as a preparatory study, this sheet likely served an independent purpose, intended either as a finished presentation drawing or as part of a collector’s portfolio celebrating the grandeur of Roman antiquity — a common intellectual pastime in Enlightenment Italy.

Le Magazine de PROANTIC

Le Magazine de PROANTIC TRÉSORS Magazine

TRÉSORS Magazine Rivista Artiquariato

Rivista Artiquariato