Étienne Doirat (c. 1670-1732) was a talented and prominent French cabinetmaker of his time. Whereas he had a career of over thirty years, he is mostly associated with the Régence period (French Regency). The Régence, despite being a short period on the paper (1715-1723) was very interesting artistically speaking, a time of exploration after the death of Louis XIV and before the glorious Rocaille style associated with Louis XV.

This imposing stamped commode kept at the Getty Center is among the most exquisite identified works of Étienne Doirat (Public Domain).

The French Régence

After 72 years of reign, Louis XIV dies on September 1, 17175. There is a large sense of relief in France after the dragging crepuscular last years of the Sun King. The country is financially exhausted because of incessant wars. The court is gloom between the deaths of three royal heirs in 1711-1712 and the religious austerity encouraged by Madame de Maintenon, the morganatic wife of Louis XIV since 1683.

The new King Louis XV, great-grandson of Louis XIV, is only five years old in 1715. Philippe d’Orléans (1674-1723), nephew of Louis XIV, becomes Régent. Philippe is an art lover. He is, in fact, an accomplished artist himself as a student of Antoine Coypel. He also composes music—complicated pieces as he wrote three operas.

Philippe d’Orléans, Le Régent by the workshop of Jean-Baptiste Santerre, c. 1717. © Galerie Nicolas Lenté

Maybe this creative facette explains his inclination to new ideas. Until 1718, he governed through polysynody, giving more space to the aristocracy. He also adopted John Law’s system using paper money to replenish the state coffers. And most importantly, he brought peace to the French kingdom thanks to a daring and smart alliance with the United Provinces of the Netherlands, England and Austria.

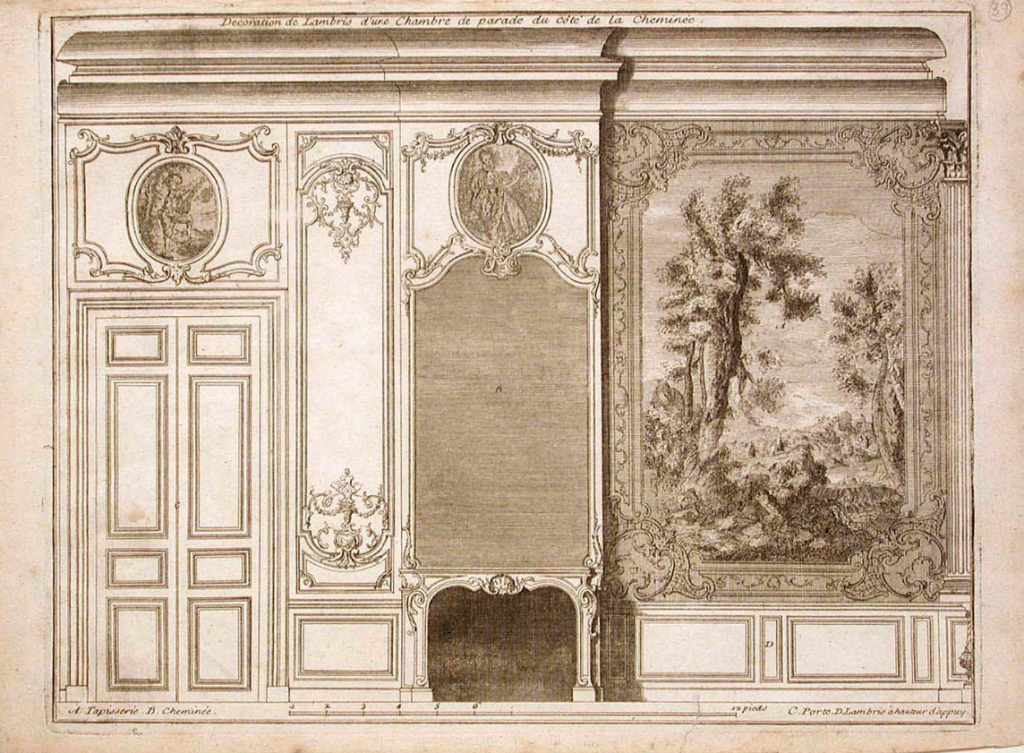

Indicative of this wind of change, the court leaves Versailles and stays in Paris until 1722. The aristocrats build or embellish their Parisian palaces. L’Hôtel d’Évreux (nowadays the Palais de l’Élysée, the French presidential residence) was built in 1718-1722. L’Hôtel de Matignon (currently residence of the French Prime Minister) was built in 1722-1724. Thus, despite a relative frugality of a state that needs saving, there is ample need to furnish and decorate in France.

Decor designed by Armand-Claude Mollet (1660-1742) in a state room of the Hôtel d’Evreux. Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields (Public Domain)

Why a Focus on Commodes During the Régence

For instance, furnish with commodes, a relatively new sort of furniture. The first model created for Louis XIV by André-Charles Boulle around 1708-1709 was entered as a bureau in the official ledger. From “table en bureau” to “bureau en commode“, the term commode (meaning convenient in French) would have prevailed after 1711 for the chest of drawers, an iconic piece of the 18th century.

Commode by André-Charles Boulle delivered in 1708 for Louis XIV’s bedroom in the Grand Trianon. © Château de Versailles, Dist. RMN / © Christophe Fouin

It is interesting to explore the metamorphosis of the commode, from the commode en tombeau (a model attributed to Alexandre-Jean Oppenordt, even anterior to the 1708 Boulle’s piece, is unambiguously inspired by a sarcophagus) to the sauteuse with two drawers and cabriole legs iconic of the Louis XV style. The French Regency was this time of exploration of shapes, materials and visual effects. When we think about it, representing the Régence as a time of hybridation or transition is unfair to the creators of that time. We know what came after. They didn’t. They are experimenting many combinations, playing furniture darwinism without knowing it.

A typically Louis-XV stamped drawer chest in lacquer by Mathieu Criaerd (1689-1776). © Galerie Bordet

The Chest of Drawers by Étienne Doirat

The quintessential, most illustrious Régence cabinetmaker is Charles Cressent (1685-1768) as he was officially at the service of Philippe, duke of Orléans. It should not overshadow numerous other craftsmen who supplied people of means.

In 1923 when the Comte de Salverte wrote “Les ébénistes du XVIIIe siècle, leurs oœuvres et leurs marques”, not much was said about Etienne Doirat. However, in 1985, Jean-Dominique Augard published a very informative paper about Étienne Doirat including an inventory made just after his death in 1732. The timing of Doirat’s life to understand furniture of the French Regency is very relevant. Doirat, characterized as “menuisier en ébène” in his marriage contract, had a long career of roughly thirty years, his death happening only nine years after the end of the Régence (Louis XV is only 22).

A print made around 1700 represents a French carpenter cabinetmaker with his tools and Boulle-style clothes. © Bibliothèque nationale de France

Based on his post-mortem inventory, out of approximately 200 pieces, 44 of them are chest of drawers (31 are finished and 13 need completion). The two expert cabinetmakers in charge of his inventory are Gaspard Coulon and the illustrious Antoine Gaudreaus (1680-1746), cabinet maker of Louis XV.

Let us now have a closer look at the chest of drawers made by Doirat to understand the variety of his creative explorations while attempting to summarize the most common characteristics of his commodes.

For this exercise, we selected five commodes, including three carrying his estampille (stamp). Even though stamps were theoritically mandatory since 1637, it was not followed closely. However, stamping grew in practice in the 1720s, i.e. before the injunction of the Furniture-Making Guild in 1743. Consequently, stamps are not pervasive on Doirat’s work. It only concerns the last part of his career. And when he stamped, we don’t know if he did it sporadically or consistently. It was a very unequal practice, even among cabinet makers of that period. For instance, Cressent never stamped.

Five commodes by Etienne Doirat. Top left: J. Paul Getty Museum (Public Domain). Top right: © Antiquités Saint Nicolas. Bottom left and right:© Galerie Pellat de Villedon. Bottom in the middle: Petit Palais (Public Domain).

Commode Shapes

In the inventory, Coulon and Gaudreaus described Doirat’s chests of drawers in three ways: commode “en tombeau“, “à la Régence“, or “en Esse“. As much as it does not give us enough elements to define precisely what each term meant for them, it shows that for cabinetmakers of that time “en tombeau” was different from “à la Régence” whereas today they tend to be used interchangeably. At least, it is clear that the overall shape is essentially about curves, experimenting them in all places in the front and sides. That is where we can see the largest diversity in Doirat’s work.

When the number of drawer rows are mentioned in the inventory, it is always three with a total of three or four drawers (in the latter case, two short drawers on top). It certainly says a lot about the high proportion of three-drawer commodes he made. However, we also know of two-drawer chests by Doirat. One of them, conserved in the Petit Palais in Paris, is included in our selection.

Several commodes with three drawer rows. Their front exhibit bombé and serpentine curves. Left: Getty Center. Middle: © Galerie Pellat de Villedon. Right: © Antiquités Saint Nicolas.

With three drawers, there is more room for horizontal curves. The bombé curves can be positioned high or towards the middle impacting the size of the top drawer(s). When the undulation is essentially vertical, the most common design is a serpentine front (associated with console legs) rather than an oxbow front. Doirat doesn’t seem to have shown much interest in exploring where the commode mazarine could go, or maybe did, but quickly saw that it was not a promising path. A stamped specimen in the Bamberg Neue Residenz (which disappeared during the 2nd World War) would come the closest to a mazarine inspiration.

Doirat, having fun with all the surfaces of a commode, also experimented with its bottom shape. Whereas most of his chests have an ornated apron, there are some examples of “commode à pont” where the middle section is arched leaving a smaller drawer on each side. This is probably a variation of the commode en tombeau where some models had two drawers in the bottom row with a space in the middle, sometime recessed, devoted to ornaments (the so-called commode à moustache). We can envision how the middle section of a commode à moustache could be removed to lighten it and create a unique and architectural design.

Comparison of two Etienne Doirat’s drawer chests: the commode à pont emerging from a commode à moustache. Left: © Galerie Pellat de Villedon. Right: © DANTAN.

Woods

In his 1732 stock, Doirat had 18 different types of exotic or indigenous woods. Exotic woods (amaranth, rosewood, kingwood, satinwood, tulipwood, ebony, mahogany…) were used for veneer. The structure was made in fir and/or oak. Most of the drawers were in walnut.

Close-ups on the wood. Top left and right: Kingwood. Bottom left: Rosewood . Bottom right: Kingwood and amaranth.

Veneers in matching patterns are a hallmark of the French Regency period. Doirat likes associating banding, stringing, and diamond match (also, reverse diamond or book match). All the hues of the wood can shine with an astonishing moiré effect. The geometric and fondu background gives enough space to the gilt mounts.

With Doirat, you will not see any floral marquetry or lacquer.

Bronze Mounts

Gilt mounts are essential to Doirat’s work. He was not a sculptor like Charles Cressent was. However, mounts were so fundamental to his style that he had them cast specifically for him. Again, based on the post-mortem inventory, his own lead mount models were found in his workshop. Of course, his mounts may have been copied and used by other artists.

Etienne Doirat used espagnolettes extensively. Left: Petit Palais (Public Domain). Middle: © Antiquités Saint Nicolas. Right: J. Paul Getty Museum (Public Domain).

We do not know of a commode of his without gilt-bronze sabots whether they be acanthus leaves or scrolls. Another common feature of Doirat is the espagnolette (female head and bust) leg mounts, most likely inspired by Cressent’s. They are, of course, not present on all of his work, and are typically Régence.

Could the female characters developed by Antoine Watteau in the “Pélerinage à Cythère” (1717) be an inspiration for the espagnolettes of Charles Cressent after 1720? Details of the painting in the Musée du Louvre © RMN-Grand Palais / Stéphane Maréchalle.

When it comes to the fronts, most of the mounts are similar on all the drawers showing total symmetry. Yet, some drawer chests have a central cartouche running over two drawers and the skirt (seen on the Getty Center’s commode). This decorative choice certainly happened towards the end of his career as another influence of Cressent.

Overall, the other mounts (drawer pulls, escutcheons, mascarons on the apron), tend to be more in the style of Boulle—with mythological and solar inspiration—than rococo.

Mascarons are reminiscent of Louis XIV’s style. © Galerie Pellat de Villedon

Étienne Doirat, a Busy and Recognized Parisian Cabinet-Maker

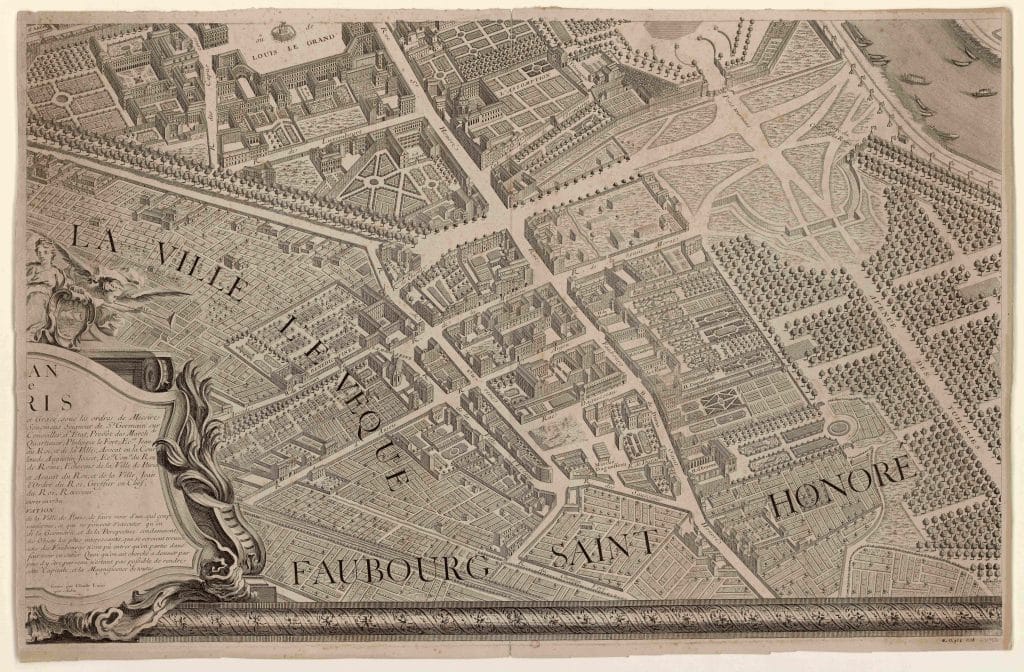

M. Doirat was living at the center of all the action when it comes to cabinet making. His family settled in the faubourg Saint-Antoine in Paris at the end of the 16th century (or early 1600s). Craftsmen in this district were under the protection of the abbey of Saint-Antoine-des-Champs: since the 15th century, they had a privileged status allowing them not to follow guild regulations. Workers could come from provinces or foreign countries and apply their talents with more freedom. This area was a thriving hub for decorative arts.

In his workshop in the faubourg Saint-Antoine, Doirat had 11 workbenches for his employees. It is a large number. To give some perspective, André-Charles Boulle had up to 20 workbenches but only seven in 1732. In 1737, Bernard I van Risenburgh had seven workbenches too.

Doirat also had towards the end of his life a shop rue Saint-Honoré managed by his son in law (cabinetmaker as well), Louis-Simon Painsun. This is the chic district of Paris today. It was already the case in the 18th century. This street is in the vicinity of the Hôtel Matignon and Hôtel d’Évreux we talked about earlier. You can imagine his clientèle.

District around the Faubourg Saint Honoré in 1739. Fragment of Turgot’s map of Paris. Musée Carnavalet, Histoire de Paris (Public Domain).

We know that Pierre IV Migeon and Antoine Gaudreaus resold Doirat’s furniture. Gaudreaus owed 600 livres to Doirat when the latter deceased, probably because he was supplying Gaudreaus for the Garde-Meuble de la Couronne. Other marchands-merciers in Dijon, Bordeaux and Avignon (again, based on who owed him money when he died) were among his customers and several of his works have been found in the Bamberg Neue Residenz.

Despite having only fragmentary knowledge about Étienne Doirat, we know he was an important qualitative cabinet maker of his time. This is paramount to cast the light on craftsmen other than the official royal suppliers. It helps understand how styles and inspirations were harmonizing over the same period as well as the connections and influences among artists and artisans.

####

This articles owes a lot to the paper (in French) of Jean-Dominique Augarde: “Etienne Doirat, Menuisier En Ebène.” The J. Paul Getty Museum Journal 13 (1985): 33–52.

####

You May Like

Etienne Doirat | Régence (French Regency) | Louis XIV to Louis XV Chest of Drawers | 18th-Century Furniture | 18th-Century Art & Antiques