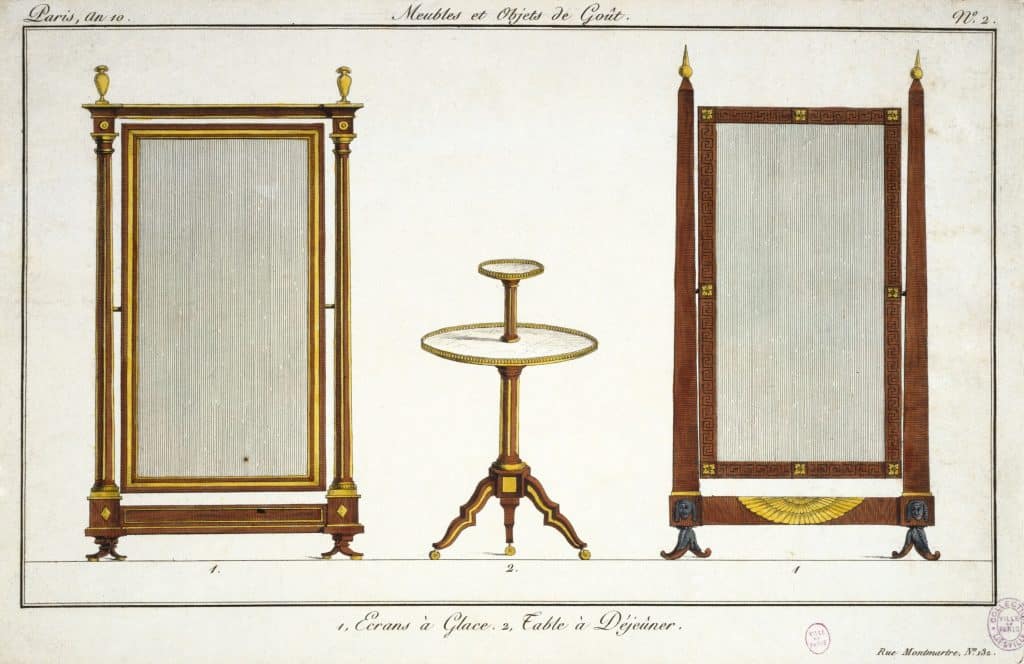

This psyché dressing mirror attributed to Guillaume Benneman (1748-1811?) is a magnificient statement piece for many reasons. It is an opportunity to study not only this mirror, but also the emergence of this new type of furniture towards the end of the 18th century. Moreover, it was the perfect occasion to develop on Benneman, a major cabinet-maker of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette.

This psyche dressing mirror in mahogany is attributed to Guillaume Benneman. © Igra Lignum

An Early French Cheval Glass, Late 18th Century

First, this mirror is remarkable because it is an early specimen of a cheval mirror. It is in a beautiful state of conservation despite full-length swivel mirrors being structurally a fragile type of furniture.

Before we address how cheval mirrors came to existence, let us have a tour of this rare dressing mirror, an exciting piece because it was likely created during the Directoire, a short period between Louis XVI and the first French empire. The Directoire, from 1795 to 1799, took place after the death of Robespierre and before Napoleon’s coup establishing the Consulat.

We can recognize traits of the Louis XVI style. The most striking is the fluted columns framing the glass with two urn finials. After the 1783 Treaty of Paris that ended the American Revolution, importation of mahogany from the West Indies was facilitated. The alliance of mahogany and copper became a classic of the late Louis XVI period.

Attributes of Louis-XVI style: Urn finial, fluted column, mahogany and copper. © Igra Lignum

The lion paw feet stand out not only because they are ebonized, but also by their style. They announce the Consulat and early First Empire “return from Egypt” style. In 1798, Napoleon Bonaparte was sent by the Directoire to lead an expedition in Egypt. Thus, the pieds en jarrets—echoing ancient Egypt—are a distinctive avant-garde touch in this mirror. However, let us not forget that such feet could sometimes be found during Louis XVI’s reign (for instance used by Georges Jacob or Pierre Gouthière). Note the small castor wheels that add a convenient mobility to the mirror.

Attributes of Consulat / Empire styles: Lion paw feet, stylized guilloche. © Igra Lignum

The guilloche motif is noteworthy as well. Louis XVI furniture was not short of them. In our case, the stylized interlaced frieze is quite unique. It looks like a transposition of a pierced brass gallery used on occasional tables or some fall-front desks in the 18th century. It has a modern geometric feel fitting the Directoire grammar. In the simplicity of this pattern, we sense the etruscan influence so in vogue already at the end of Louis XVI’s reign and visible, for instance, on the Sèvres porcelain service created for the Laiterie de Rambouillet of Marie-Antoinette delivered in 1787.

Psyché Dressing Mirror or Cheval Glass: What Is It?

Psyché… Cheval mirror… Not that we mean to bore you with lexicology and definition, but the origin and evolution of the names (both in French and English) is quite relevant to the creation and context of this mirror.

Psyché is the French term for a full-length dressing mirror that can be tilted. It is short for “mirror of Psyche” in reference to the myth of Psyche and Eros where Psyche was known to have looked at a reflection of her entire body.

Psyche looking at herself in a mirror in the myth of Eros and Psyche. 18th century drawing attributed to Barbier. © Galerie Etienne Thuriet

The large glass mounted in a first frame swivels in a larger frame with a trestle base. It is one of the rare new types of furniture created during the Directoire (1795-1799), if not towards the end of Louis XVI’s reign. In English, the name cheval mirror betrays the French origin of the object as cheval means horse. It is used here for the frame mounted on four legs reminding the animal (as in chevalet).

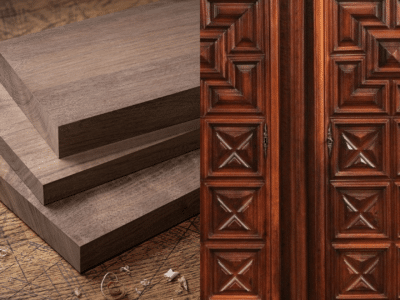

Thanks to castle inventories, we know that before being called psyché around 1810, this type of mirror went by the names of “glass screen” (écran à glace in French) or sometimes “toilet mirror with screen” (miroir de toilette à écran). Interestingly, the illustration in the 1802 first edition of Collection de meubles et objets de goût by Pierre de la Mésangère (used as an interior design fashion guide of the time) inserts an écran à glace astonishingly similar to the cheval mirror we are presenting in this article.

The écran à glace on the left is like a twin to our cheval mirror. Found in the book “Collection de meubles et objets de goût” published by Pierre Joseph Antoine Leboux de La Mésangère (1761-1831). CC Paris, Musée Carnavalet

The “screen” (écran) part of their name gives us an indication of their origin. They were inspired by the screens placed in front of fireplaces (hence their shape) where the fabric in the middle got replaced by a mirror.

Original giltwood and tapestry for this Louis-XVI period fireplace screen. © Antiquités Martin

At the end of the 18th century in France, mirrors became very fashionable—while remaining a luxurious element of decor only the wealthiest could afford— thanks to the tremendous technical and economical development of the Manufacture royale de glaces de miroirs (created by Louis XIV in 1665) that crushed the Venitian monopoly. Large mirrors like trumeaux mirrors or pier mirrors took the place of tapestries and paintings (especially history paintings).

From there, mirrors were also integrated in furniture that could be moved instead of being set in one specific place. In “Arthur Young’s Travels in France During the Years 1787, 1788, 1789”, the author wrote in one of his interior descriptions:

The drawing-room very elegant (gilding always excepted).—Here I remarked a contrivance which has a pleasing effect; that of a looking-glass before the chimnies, instead of those various screens used in England: it slides backwards and forwards into the wall of the room.

Mirrors, including cheval mirrors, went along the development of more private spaces like boudoirs and dressing rooms. Cheval mirrors were particularly chic and fashionable during the first Empire in France and the Regency in England. They enjoyed a new popularity between the two world wars and can be especially found in the Art Deco style.

Guillaume Benneman, Ultimate Royal Cabinet-Maker of the 18th Century

This remarkable dressing mirror attributed to Benneman (also spelled Beneman) is an opportunity to introduce an important cabinet-maker of his time whose name did not cross the centuries with the same grace as Riesener, Jacob or Weisweiler, maybe because we know fairly little about this talented craftsman.

Still, below look at this admirable and truly unique medal cabinet created for Louis XVI. It integrates wax panels (remember how we talked about the forgotten art of wax) on which plants, feathers, and butterfly wings were applied and protected by glass. Intriguing, isn’t it?

How imaginative this medal cabinet is! It was commissioned personally by Louis XVI shortly before the Revolution for the Vaisselle d’or room in Versailles. © Château de Versailles, Dist. RMN / © Christophe Fouin

Benneman became the main and ultimate cabinet-maker of the Garde-Meuble de la Couronne after the disgrace of Riesener around 1784. The latter had become evidently too expensive for a court required to spend more wisely in a time of deep economic crisis.

Benneman, born in North Westphalia in 1748, became master in Paris in 1785. Many cabinetmakers were originally German in the France of Queen Marie-Antoinette. From 1786 on, inaugurating a new system of régie under the supervision of the sculptor Jean Hauré, his workshop with ten workbenches was located rue du Forez in the Marais. He delivered over 2,000 pieces to the Garde-Meuble de la Couronne between 1786 and 1792. The last mention of his name found (so far) is 1804.

He essentially worked with mahogany, but also used ebony or other exotic or fruit woods. He was known to combine sturdiness and elegance in impeccably proportioned pieces and worked with the best artists (such as Pierre-Philippe Thomire) for finely chiseled bronze mounts or other decorations. He was a precursor of the Empire style and his furniture was still used by Napoléon Bonaparte and Eugénie.

His most iconic pieces must be the commodes created in 1786 for the Queen located in the château de Fontainebleau. Based of an original commode made by Joseph Stöckel, it was transformed and re-decorated including some Sèvres porcelain panels. This model inspired numerous high-quality copies in the 19th century. Let us give you two examples found on PROANTIC. Truthful to the originals, they are in mahogany with extravagant gilt bronze ornaments of foliage, garlands and a lion escutcheon. The most evident difference is the front and side medallions.

The central medallions on each side are in bronze, based on Bacchus childhood by Clodion. © Frédéric Granger

The porcelain medallions signed by Polyet depict Marie-Antoinette and Louis XVI. © MDRS Antiquités

####

The two main sources for this article (out of many more):

- Book: Melchior-Bonnet, Sabine (1994). Histoire du miroir. Imago, 288p.

- Web site: Benneman, ultime ébéniste de Louis XVI (announcing the objective of a monograph on Benneman)

####

You May Like

Mirrors | Benneman | Jacob Frères | Georges Jacob | Stöckel | Riesener | Weisweiler | Gouthière | Thomire