Follow the vibrant trail of Post-Impressionism through Provence, a region whose dazzling light and landscapes became a crucible for artistic revolution. From Van Gogh in Arles—guided by his admiration for the Marseille-born painter Monticelli—to the Neo-Impressionists and Fauves along the shores of Saint-Tropez, and the Expressionists in Marseille, Provence offered endless inspiration.

Just as Normandy nurtured the Impressionists, Provence fueled the Post-Impressionists with its blazing luminosity, radiant flowers, ochre soils, rugged hills, and shimmering sea. Here, artists like Signac, Cross, and Matisse unleashed bold explosions of color that reshaped modern art. And perhaps, in their footsteps, one can still glimpse the echo of Van Gogh’s dream of a “Midi School” of painting.

In this journey through Provence, we will encounter the masters who shaped the region’s artistic legacy: Van Gogh, Cézanne, and Monticelli; the Pointillists Signac and Cross; the Fauve Matisse; and Provençal painters such as Camoin, Manguin, Girieud, Seyssaud, Chabaud, Verdilhan, and other members of the Péano group.

Van Gogh’s Provence, the Influence of Cézanne and Monticelli

In February 1888, Vincent Van Gogh decided to move from Paris to Arles. As he wrote to his good friend Emile Bernard: “It is in the South now that the studio of the future must be established.” He dreamt of an artist colony, maybe similar to what took place in Brittany’s Pont-Aven around Paul Gauguin.

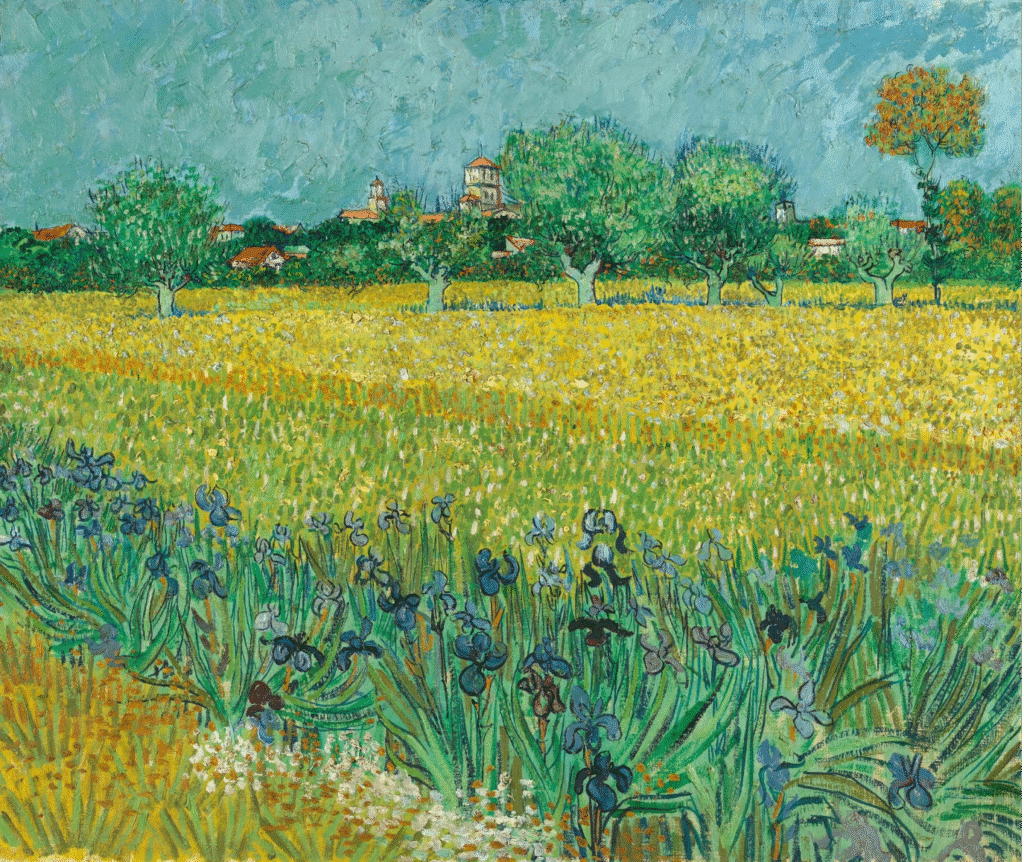

Vincent Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo that he loved the blue and yellow of Provence. This is visible in this view of Arles with irises in the front against a yellow field, olive trees and Arles in the background. © Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Vincent Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo that the Southern luminosity inspired him in “the land of blue tones and cheerful colors, where there is more color, more sun.” He was also aspiring to find in France a place similar to Japan in terms of colors, and in his mind, it was the South in Provence.

The country seems to me as beautiful as Japan, with the limpid atmosphere and the effects of cheerful color. The waters make patches of a fine emerald and a rich blue in the landscapes, just as we see in the Japanese prints. Pale orange sunsets making the fields appear blue. Splendid yellow suns. Yet I have scarcely seen the country in its usual summer splendor. The women’s costumes are pretty, and on Sundays especially one sees along the boulevard arrangements of color that are very naïve and well found. And that too, no doubt, will become even more lively in summer.

—Vincent Van Gogh (in a letter to Emile Bernard)

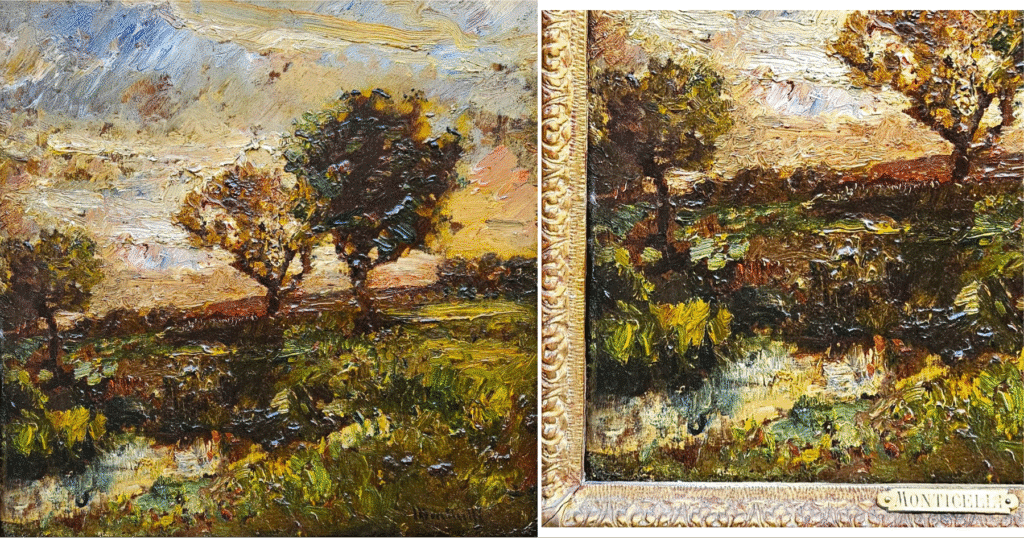

Van Gogh was a great admirer of Paul Cézanne and worshiped Adolphe Monticelli (1824-1886), who respectively lived in Aix-en-Provence and Marseille, about 80 kilometers away from Arles. Many may not realize today the fame of Monticelli during his most glorious days. That is why it may be necessary to remind that he was held in the highest esteem by renowned collectors and critics such as Paul Verlaine, Marcel Proust, or Robert de Montesquiou.

Writing to Albert Aurier, an art critic who published a dithyrambic article about his work in the Mercure de France in February 1890, Van Gogh nearly apologetic, wrote: “Yet I feel uneasy when I think that what you say would redound to others rather than to me. For instance, Monticelli above all. Speaking of him: as far as I know, he is the only painter who perceives the chromaticism of things with such intensity, with that metallic, gem-like quality.”

This painting of Monticelli depicts the same landscape as in Sunrise and Sunset in the National Gallery’s collection in London. © Galerie Guardia

Looking at Monticelli’s painting above, we can understand the influence of his brushstrokes, impasto (and even colors) on Van Gogh’s style when he painted, for instance, the Sunflowers, Bushes, or Red Vineyard while in Arles.

Cézanne admired Monticelli too; from 1878 to 1884, Monticelli and Cézanne had long escapes to paint en plein air together. The painter André Maglione (1838-1923) wrote about Cézanne and Monticelli’s relationship in his 1903 book, “Monticelli intime, de 1871 à sa mort”—Auguste Lauzet, painter and engraver from Marseille, also reported it.

How Neo-Impressionism Evolved With Signac and Cross Around Saint-Tropez

Following the dramatic episode of Van Gogh cutting his ear in Arles, Paul Signac (1863–1935) visited him in the hospital on March 23–24, 1889. Soon after, on April 8, he wrote to Van Gogh: “My dear friend, after wandering along the coast, I’ve settled in Cassis.” For Signac, an avid sailor, the lure of the Mediterranean was irresistible. Cassis served as his harbor in 1889, but from 1892 onward—and for the next two decades—Saint-Tropez became his true refuge, where he spent nearly half his time. It was Signac who placed Saint-Tropez firmly on the artistic map.

His friend Henri-Edmond Cross (1856–1910) likely influenced his choice of the Saint-Tropez area, as Cross had been frequenting the French Riviera since 1883. In 1891, Cross moved to Cabasson in Provence—near Le Lavandou, where he would later settle—just 40 kilometers from Saint-Tropez.

Watercolor by Henry-Edmond Cross using the Pointillism technique to depict a maritime landscape of Provence in Le Lavandou in 1901. © Galerie Meier

To describe his Plage de la Vignasse painting, Cross wrote to Signac in 1892: “It is to tell you, however, that I believe I have taken a step toward the charms of pure light… A foreground of sand scattered with everlasting flowers and grasses—the mauve sea with the reflection of the sun around four o’clock in the afternoon in summer—an ashen orange sky.” His paintings from this period seem to dazzle us with sunlight.

It was a time of profound loss for Signac. Between August 1890 and March 1891, he saw three close painter friends—Dubois-Pillet, Van Gogh, and Seurat—pass away. Craving a fresh start and new inspiration, he left Paris behind and, in May 1892, arrived in Saint-Tropez aboard his sailboat, Olympia.

Paul Signac is not the creator of divisionism and pointillism; Georges Seurat is. However, Signac was a relentless evangelist of the Neo-Impressionist movement (as coined by the visionary art critic Félix Fénéon in 1887). He defined the principles and sources of this new art in his work entitled “From Delacroix to Neo-Impressionism” (1899). As such, he had the aura to create an artistic pole of attraction in Provence, if not the “studio of the future” as dreamt by Van Gogh.

Divisionism, as invented by Seurat, was a rigorous painting discipline based on a scientific approach to color (inspired by theories of Eugène Chevreul, Charles Blanc, and Ogden Rood). It is characterized by the technique of “the division of color”. Seurat advocated painting with small juxtaposed dots of pure colors, similar to points, and selecting specific colors to create contrasting visual effects.

While in Provence, Cross and Signac freed themselves from the original rigor of Divisionism. The points lengthened to become dabs, more like commas or sticks. The palette evolved towards bolder colors, intense as the Mediterranean sun. The landscapes scintillate with a vibrant light. After the mid-1890s, Cross and Signac progressively turned towards watercolors, either for studies while outside or for completed and exhibited works. It allowed for more spontaneity and freedom with colors. White, untouched background spaces of the canvas or paper started to show.

Saint-Tropez and the Neo-Impressionist Roots of Fauvism

The evolving and experimental approach to color of Signac and Cross also played a role in the beginning of Fauvism. Neo-Impressionism liberated Henri Matisse (1869-1954) in his treatment of color.

In 1904, Matisse spent two months in Saint-Tropez close to Signac and visited Cross in Le Lavandou. He was introduced to pointillism by the masters themselves, explaining why his paintings “Luxe, calme et volupté” went to Paul Signac and “Parrot Tulips” to Henri-Edmond Cross (while Matisse owned “La ferme, matin” painted in 1893 by Cross).

The next summer, in 1905, Matisse and André Derain (1880-1954) joined in Collioure to blaze their own artistic trail. However, Derain indirectly acknowledged their legacy (and difference) when he wrote to his friend Vlaminck that they were trying “to wring out everything tonal division had in its skin.” While they were in Collioure, it was the turn of Matisse’s artist companions Charles Camoin, Henri Manguin, and Albert Marquet to spend time in Saint-Tropez with Signac.

Henri Matisse experimented with Pointillism in his painting “Luxe, calme et volupté”. © Succession H. Matisse Photo: Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Philippe Migeat/Dist. RMN-GP

The same year, from mid-October to mid-November, these five artists (Matisse, Derain, Manguin, Marquet, Camoin) as well as Vlaminck, Girieud, Rosen and Pichot presented artworks in Room 7 of the 1905 Salon d’Automne in Paris, the room called the “cage aux fauves” (wild animal cage) because the critic Louis Vauxcelles wrote in Gil Blas on October 17, 1905 about sculptures by Albert Marque: “The candor of these busts is striking amid the orgy of pure tones: Donatello among the Fauves…”

Fauvism was born, a shocking artistic vision for some who did not appreciate the bright colors that did not correspond to reality. For them, as described by Camille Mauclair, their paintings felt like “a pot of paint […] thrown to the public’s face.” For Matisse, the decorative function of art was central to his compositions.

Continuing to leverage the news article by Vauxcelles, it was a well-known fact, right from the start, that this group stayed in “[…] Saint-Tropez. They all hurried there, like a flock of migratory birds. It was in the spring of 1905: a brave little colony of painters, painting and conversing in this enchanted land—Signac, Cross, Manguin, Camoin, Marquet.”

Thus, there is no doubt that Saint-Tropez was an outstanding location for France’s first contemporary art museum, today known as the Annonciade Museum. It was considered “contemporary” because the celebrated artists were still alive when it was founded in 1922 by Henri Person (1876–1926), who shared a deep friendship with Signac, united by their love of art and sailing.

The First Fauves From Provence: Camoin, Manguin, Girieud

Speaking of the most famous masters of Fauvism is one thing. As this article focuses on Provence as a source of inspiration, it offers a wonderful opportunity to highlight those Fauves mentioned by Vauxcelles who had a profound connection with the region, either because they grew up there or chose to settle there permanently.

Charles Camoin (1879-1965)

Camoin was from Marseille. When he got accepted to the École des Beaux-Arts de Paris in 1898 in Gustave Moreau’s workshop, he formed a long-lasting friendship with Marquet, Matisse, and Manguin. However, he is the only one of them to have developed a strong bond with Cézanne, who was like a fatherly mentor to him.

In 1901, during his military service in Aix-en-Provence, he visited the maestro. Cézanne appreciated him dearly and invited him repeatedly for lunch on Sundays. Léo Larguier reported that Cézanne would have said the first time he saw studies of Camoin: “Damn, he’s talented, that guy! He’ll have to have my back when he returns to Paris…”

With a refined sensitivity to form and color, Charles Camoin wove into his work the influence of Cézanne and Renoir in his own distinctive way. Oil on canvas titled in the Camoin archives as “Fruit bowl and coffee pot, circa 1935”. © Violon d’Ingres

Calling himself a “Fauve at liberty”, Camoin rarely transposed colors. With a cezannean influence, he combined bold colors with lively volumes. We see it in the still life presented here, which also integrates Renoir’s influence with smaller, more precise strokes.

Or as Vauxcelles wrote (in the same article cited above): “Mr. Camoin constructs paintings brimming with a robust, vigorous energy; […] bold and assured contrasts; a clear, direct candor, with a color that does not deceive.”

Henri Manguin (1874-1949)

Manguin acquired a sense of chromatic freedom early on, even before the Fauves were recognized as such. Harmony and serenity permeate his work—whether in a landscape, a nude, or a portrait (often of his wife Jeanne, reading or lost in reverie). It is a kind of modern Arcadia, for which Provence offered the perfect setting.

Manguin, a native Parisian, first discovered Saint-Tropez in 1904 while staying in a villa next to Signac’s and deeply fell in love with the South. So much so that he later purchased a property named L’Oustalet in Gassin, on the heights of Saint-Tropez, where he would spend his final years.

The South has been, I believe, a good teacher for me, and I return, if not satisfied with myself, at least with a sense of great beauty and an understanding of many things hitherto unknown.

—Henri Manguin (Letter to Henri Matisse from Saint-Tropez on September 21, 1905)

An idyllic 1924 view of Gassin in watercolor by Henri Manguin. It comes with a certificate of authenticity by his granddaughter, Claude Holstein Manguin. © Galerie Alexis Pentcheff

In his famous article on the 1905 Salon, Vauxcelle wrote of Manguin that he showed “still too many echoes of Cézanne; yet already the stamp of a powerful personality.” The watercolor above is a telling and charming example of his personal style: purple, a color he favored more than most, is present; his assured talent for watercolor is clear in the many works he produced; and here, he depicts his beloved Gassin.

Pierre Girieud (1876-1946)

Although Pierre Girieud is listed among the Fauves in Louis Vauxcelles’ article and was familiar with “Matisse’s group” as well as the Parisian avant-garde, he was not counted among their close friends. As André Salmon wrote in Le Salon des Indépendants, Paris-Journal, 18 March 1910: “Girieud is a Fauve despite himself—that’s what he was called, and he didn’t protest.”

Self-taught and buoyant in spirit, Girieud drew inspiration from a diverse array of sources. Like Van Gogh, he admired Monticelli—and Cézanne, too. He also absorbed the style of the Nabis, especially Gauguin, whose work he discovered in 1901. In his paintings, he introduced broad, flat planes of color outlined with strong, defining contours.

As written by Girieud on the back of his painting Cadenet, Orage sur l’Acropole: “To Mr. Charles Garibaldi to thank him for the love he has always professed for the Eminent Monticelli. August 19, 1948.” Girieud wrote this four months before he passed. © Galerie Guardia

Exhibited by Berthe Weil as early as 1901 and by Kahnweiler in 1907, Girieud met his friend Kandinsky in 1904. The first Frenchman to embrace the principles of the Neue Künstlervereinigung München (NKVM) at its founding in 1909, he then served as a link between the Parisian avant-gardes and the German Expressionists. He also participated in the beginnings of the Blaue Reiter in Munich in 1911.

Vauxcelle wrote in 1905 of Girieud’s paintings at the 1905 Salon: “Mr. Girieud is a lyricist who stylizes hydrangeas, peonies […] by enlarging them. His palette is flamboyant.” From 1902 to 1909, flower bouquets were among his favorite themes. How not to think of Van Gogh when looking at them?

The dazzling colors used by Pierre Girieud for “Chrysanthemums on blue background” in 1909. Oil on canvas. © Galerie Guardia

During ten years in Paris, he was an active figure in Montmartre, living near the Place du Tertre and making the now-famous Cabaret du Lapin Agile the hub of his social life. Alongside his friend Dorgelès, he orchestrated the mystification of Boronali—a provocative prank targeting abstract art, particularly Cubism, at the 1910 Salon des Indépendants—which earned him considerable publicity.

From a Provencal family, Girieud was incidentally born in Paris (but ‘rue de Marseille’, which is such a funny coincidence). He grew up in Marseille. After 10 years fully in Paris, he moved back to Marseille in 1911 to join his friend Alfred Lombard (1884-1973), with whom he shared a studio (12 quai de Rive-Neuve). The two accomplices also organized a modern art Salon de Mai in 1912 and 1913 with little success—the public was not ready.

Once back in Marseille, under the influence of Joachim Gasquet (a poet friend of Paul Cézanne), he reoriented his artistic interest towards the Italian Primitives and developed a passion for frescoes. When it comes to landscapes, Girieud was particularly drawn to the Mediterranean, and more specifically, as he said: “It is in Provence that I find the landscapes that move me most. They have the grace of Italy, the harshness of Spain, their own grandeur and balance. I prefer them above all others because I am Provençal and Gavot.”

Provence Landscapes Between Fauvism and Expressionism: Seyssaud, Chabaud, Verdilhan

At the turn of the 20th century, the vivid colors of Provence inspired artists exploring new, non-academic expressions of modern art. While their styles varied—as with Pierre Girieud, whose affiliations shifted over time—they shared a deep bond with the region’s landscapes. Their ties to Fauvism and Expressionism, combined with their singular vision and passion for capturing Provence’s spirit, make their work especially compelling. Lovers of the region, its light, and its colors will find their hearts lifted by these striking, emotive landscapes.

René Seyssaud (1867-1952)

Seyssaud is recognized as a forerunner of the Fauves. He painted his native Provence tirelessly, especially landscapes that paid homage to the cultivated land and the peasant world at a time of rapid modernization. He also painted seascapes depicting the roughness of the mineral world mingling with the sea.

Most of his paintings convey tremendous vital energy—not only through color, but also through a distinctive way of rendering depth with the layering of planes, and the visible traces of his brush. Curved lines are common in his perspectives. Beyond the dynamism they bring to the composition, they also remind us that we are standing on a globe. “Imagine Van Gogh in full fervor, Cézanne without concessions, and Monticelli a little rustic and wild,” said of him the art critic Arsène Alexandre in 1901.

Herd of the foothills of Mont Ventoux by René Seyssaud. Color and depth for this work executed using the tempera on cardboard technique, which the artist was fond of and mastered perfectly. © Galerie Marina

Born in Marseille, he entered Pierre Grivolas’ studio in Avignon in 1885. By 1897, he had held a solo exhibition in Paris, and in 1899 Ambroise Vollard offered him a contract, which he declined. From 1895 to 1921, his first dealer, François Honnorat, was a major collector of Monticelli—another reminder of the fame Monticelli enjoyed at the time, even if he is largely forgotten today. Between 1899 and 1904, he lived in Villes-sur-Ozon near Mont Ventoux, before moving for health reasons to Saint-Chamas on the heights overlooking the Étang de Berre.

Auguste Chabaud (1882-1955)

Chabaud was a good friend of Seyssaud despite the 15-year age difference. Like Seyssaud, he did his training in Avignon under the supervision of Pierre Grivolas. Still, he completed it in Paris, integrating the Beaux-Arts in 1899 and meeting Matisse, Marquet, Derain (and others) at the Académie Carrière.

With these acquaintances and the striking colors of his paintings, he is first associated with Fauvism. During his second Parisian period (1907–1914), Expressionism left a strong mark on his work: bold, forceful strokes, thick black outlines, and striking contrasts. He seemed fascinated by Parisian nightlife, including prostitution—subjects he explored in works that he kept hidden until 1950. This more grim outlook carried to his Provencal landscapes, which he didn’t stop to depict—for instance, visiting and painting with his friend Seyssaud in Saint-Chamas.

“A corner of the villa with irises” is the title mentioned on the back label of Auguste Chabaud’s studio, inventoried under the number 811. This is an oil on canvas of his beloved house exteriors, the Mas de Martin. © Galerie Marina

After the First World War and the loss of his brother, he decided to return to the family Mas de Martin in Graveson (near Avignon). He dedicated the rest of his life to Provence. He was a draftsman with a powerful graphic style, able to impart great intensity to volumes and perspectives. His landscapes often feature roads lined with quintessential southern trees—olive, pine, and plane. Drawn into the scene, the viewer travels alongside Chabaud through his beloved corners of Provence.

Louis-Mathieu Verdilhan (1875-1928)

Although artistically self-taught, the Marseille-born Verdilhan exhibited in Paris alongside Neo-Impressionists and Nabis—such as Cross, Signac, Bonnard, and Vuillard—at Bernheim’s in 1909, and with Fauves—including Matisse, Manguin, and Marquet—at the Galerie Druet in 1910.

In 1905, he founded the “Lamppost Group” (le groupe du poteau), where left-leaning artists, writers, and intellectuals gathered by a lamppost at the corner of the Canebière and Cours Saint-Louis to debate society and art. The circle included his friend, the painter Louis Audibert (1880-1983)—who would later give painting lessons to Winston Churchill in the early 1920s—along with Alfred Lombard, Abbot Cabasson, Ernest Rouvier, and others.

Verdilhan was influenced by Girieud and Lombard, with whom he shared a studio from 1910 to 1914. As explained earlier, considering Girieud’s connection with German Expressionism, Verdilhan was thus in a prime position to study it and incorporate Expressionism into his works. He began outlining in black and gradually simplifying his works.

A painting by Louis-Mathieu Verdilhan with the Huveaune river and a small village near Roquevaire, where the collector Paul Iorio lived. © Galerie Marina

In 1919, he married Hélène Casile, the daughter of the Marseille-born Impressionist Alfred Casile. Through the introduction of his friend Antoine Bourdelle, the famous sculptor, Maurice Girardin (an important modern art patron and collector) offered him the opportunity to exhibit at his Galerie La Licorne in Paris in 1920.

For this exhibition, Verdilhan presented many landscapes with a lightened color palette, where the luminous hues stand out against the black outlines. On this occasion, Paul Sentenac wrote in Paris-Journal on December 12, 1920: “The work of this artist breathes the open air, space, and the sea breeze. Louis-Mathieu Verdilhan began to paint instinctively. For a long time, in his Provence, he enclosed the light within his paintings.”

Unfortunately, Verdilhan’s promising career was cut short by cancer. Through the landscapes of Marseille, Cassis, Toulon, Sanary, Aix-en-Provence, Lascours, and Roquevaire, he captured both the sun-drenched littoral and the rolling back-country of Provence, rendering the region with a fresh, modern vision.

(Conclusion) The Legacy of Post-Impressionism in Provence: The Péano Group of Marseille

Late in their careers, Seyssaud and Chabaud became associated with an artistic circle in Marseille that met at Le Péano Bar from the late 1920s to the 1970s. Their presence hinted at a transmission between generations, though the Péano painters cannot be seen simply as their heirs. What bound this group together was less style than a shared spirit—artistic, social, and occasionally political—reflecting the anarchist and radical left ideals that some members embraced, echoing the progressive ethos once associated with the Neo-Impressionists and Fauves.

The Péano brothers ran a working-class bistro on the Old Port, which became a gathering place for locals, artists, writers, and journalists. From this setting grew a movement led by Antoine Serra (1908–1995), who in 1933 helped found the “Proletarian Painters” (Peintres prolétariens). Around him formed a close-knit circle of friends and collaborators.

“I would like to paint with the sun’s colors,” wished Pierre Ambrogiani. The pure hues, spread with his palette knife, convey a visceral connection to the Provençal soil. Oil on canvas. © Galerie Guardia

Pierre Ambrogiani (1907–1985), who at one point worked in Serra’s studio, became one of its most visible figures and counted Marcel Pagnol and Jean Giono among his friends. François Diana (1903–1993) shared his first studio with Serra, Léon Cadenel (1903–1985), and Louis Toncini (1907–2002), before settling for decades in Girieud’s former studio at 12, quai de Rive Neuve.

Other members included Louis Audibert (1880-1983), Antoine Ferrari (1910–1995), the most Expressionist among them, Hubert Aicardi (1922–1991), Jean Guindon (1883-1976), Arsène Sari (1895-1995), Edgar Mélik (1904-1976), Jean-Frédéric Canepa (1896-1981), Jo Berto, and Antoine Gianelli.

These painters depicted Provençal countrysides, portraits, nudes, and still lifes—extending the region’s artistic tradition well into the 20th century. They also turned to workers, industrial landscapes, and harbors for inspiration, yet their canvases shone with the vibrant colors of Post-Impressionism.