The elegant Art Deco sideboard attributed to Maurice Pré (1908–1988) offers a compelling point of entry into the career of a designer whose work bridges the refinement of French Art Deco and the emergence of postwar modernism. Executed in the second half of the twentieth century with exceptional craftsmanship, this piece stands as both a tribute to the legacy of Jacques-Émile Ruhlmann (1879-1933) and a reflection of Pré’s own evolving artistic language.

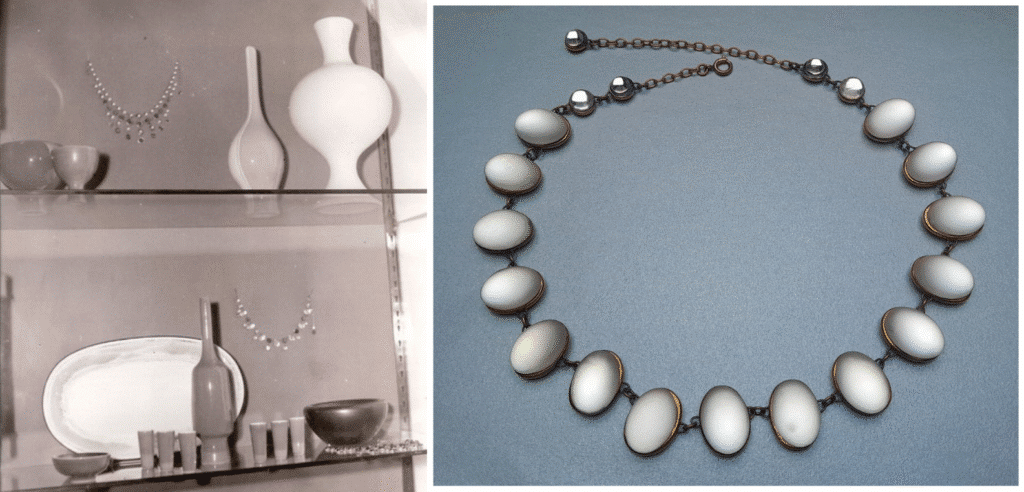

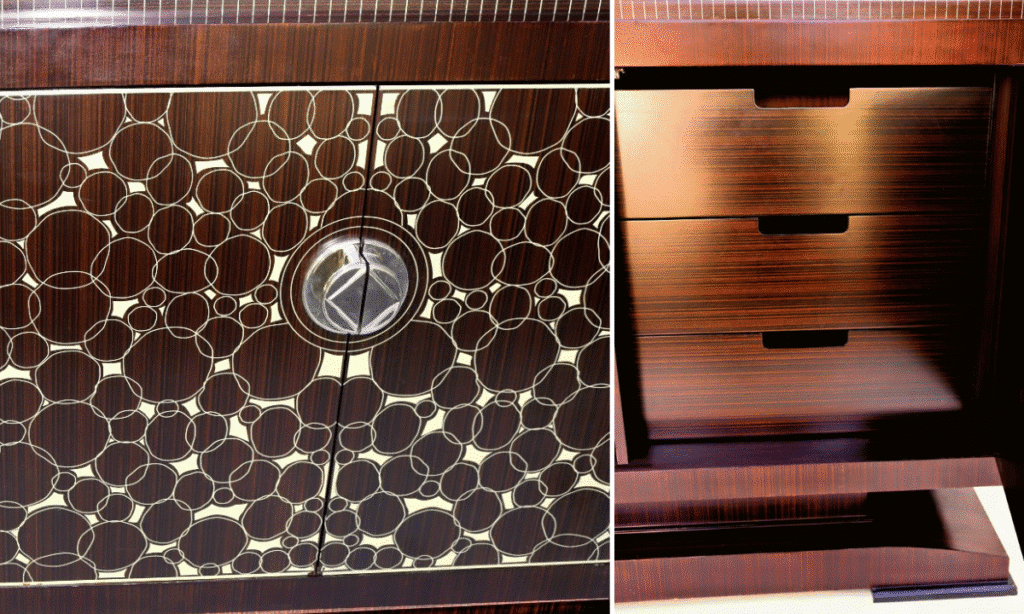

Art Deco credenza in Macassar ebony and ivoirine attributed to Maurice Pré. © Galerie Tramway

Through this object—its materials, geometry, and structure—we can trace not only a stylistic lineage but also the intellectual and professional trajectory of Maurice Pré, including his formative years in Ruhlmann’s atelier, his collaboration with his wife Janette Laverrière (1909-2011), and his lifelong engagement with the social and professional dimensions of interior architecture.

An Art Deco Sideboard in the Spirit of Ruhlmann

The sideboard attributed to Maurice Pré is an elegant and rigorously composed work. It is veneered in Macassar ebony and overlaid with a rich ivoirine marquetry forming a large geometric motif that extends across the façade and continues onto the sides. This ornamental vocabulary immediately evokes the celebrated “Élysée” cabinet designed by Jacques-Émile Ruhlmann, one of the most iconic furnishings of French Art Deco. The reference is explicit, yet not imitative: the motif is adapted, reinterpreted, and integrated into a later modernist sensibility.

This cabinet by Ruhlmann, known as “Bahut Élysée”, was delivered to the French presidential palace in 1926. It was created in 1920 and was one of the Ruhlmann pieces exhibited at the historic 1925 Decorative Arts Fair in Paris. It features varnished amboyna burl marquetry with ivory inlays, constructed on an oak carcass. Creative Commons: Photo by ThêtaBlackhole taken during the Art Deco 100th Anniversary exhibit at the MAD.

The façade of Maurice Pré’s sideboard opens through two doors whose central axis is emphasized by a modernist nickel-plated bronze mount. This metallic element recalls Ruhlmann’s use of sculptural metal plaques, notably the octagonal bronze relief designed by Simon Foucault for the Élysée cabinet, illustrating the allegory of Day and Night. In Pré’s sideboard, however, the bronze entry is more restrained, signaling a shift toward abstraction and functional clarity.

Inside, the cabinet reveals a compartmentalized interior with English-style drawers and an open niche, demonstrating a concern for rational organization and practical use. The recessed top is accented with vertical ivory fillets, while the entire piece rests on a rectangular plinth animated by a doucine molding. The proportions—1.42 meters long, 1.03 meters high, and 68 centimeters deep—reinforce the monumentality and balance characteristic of high-quality Art Deco furniture.

Facade and interior details of Maurice Pré’s Art Deco sideboard: nickel-plated mount, English drawers. © Galerie Tramway

This piece embodies a dialogue between tradition and modernity, where precious materials and refined craftsmanship coexist with a more functional, architectural approach. It is precisely within this tension that Maurice Pré’s career unfolds.

The Training of Maurice Pré and the Ruhlmann Years

Maurice Jean Albert Pré was born in Paris in 1907 into a family deeply rooted in craftsmanship. His father was a chair joiner and wood sculptor, and from him Maurice inherited both technical knowledge and a passion for fine workmanship. At the age of thirteen, he entered the École Boulle, following in his father’s footsteps. He graduated in 1924, alongside his friend Paul Beuchet, who would later become director of the school.

In 1925, Pré joined the design studio of Jacques-Émile Ruhlmann, marking a decisive moment in his formation. Ruhlmann’s atelier was one of the most prestigious environments for a young decorator, combining luxury craftsmanship with a modern vision of interior design. Pré remained there until Ruhlmann’s death in 1933, participating in several major projects, including the famed Hôtel du collectionneur presented at the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris, in collaboration with architect Pierre Patout. This project earned a bronze medal and firmly established the studio’s international reputation.

Grand Salon of the Pavillon du Collectionneur at the 1925 Paris exhibition. Furniture designed by Ruhlmann. The large cabinet is in lacquer made by Jean Dunand. © Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Album of the Collector’s Pavilion of J.E. Ruhlmann

Pré also contributed to projects such as the Paris Chamber of Commerce, absorbing Ruhlmann’s exacting standards, his mastery of materials, and his conception of furniture as an integral element of architectural ensembles. It was also in this milieu that Pré met Janette Laverrière, who joined the atelier in the early 1930s through Pierre Patout.

Maurice Pré and Janette Laverrière: A Concentrated but Decisive Collaboration

Maurice Pré’s collaboration with Janette Laverrière (1909–2011) was brief but decisive in its impact. Emerging from the intellectual and professional environment of Jacques-Émile Ruhlmann’s atelier, the couple belonged to a close circle that included Maxime Old, Jean-Denis Maclès, and Paul Fréchet. This milieu fostered a collective reflection on furniture as architecture, and on decoration as a disciplined, rational art rather than mere ornament.

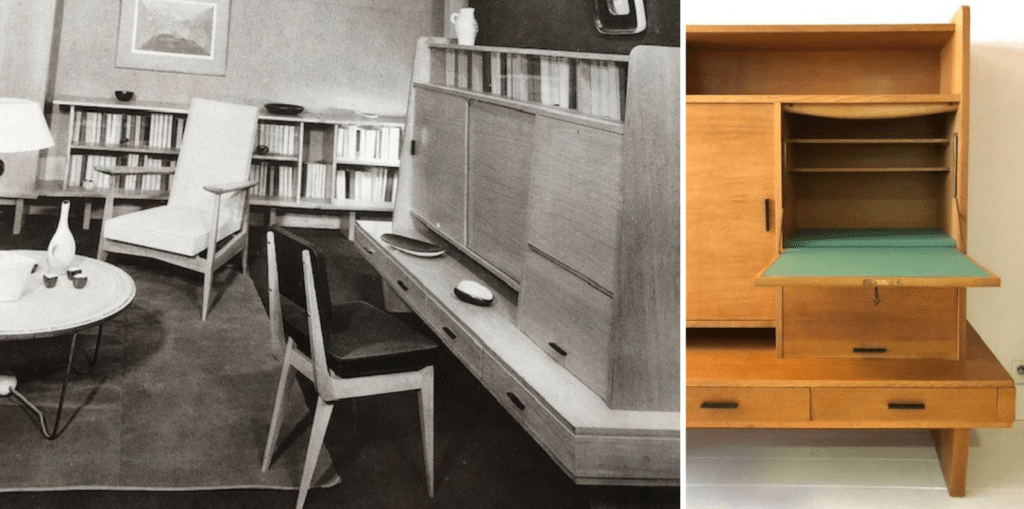

After their marriage in 1931, Maurice and Janette Pré worked jointly under the signature “M. J. Pré”, particularly during their Swiss period alongside architect Alphonse Laverrière. The projects they realized in Lausanne and its surroundings encouraged a shift toward spatial coherence and functional clarity. Furniture was conceived as part of an ensemble, responding to use, circulation, and modern ways of living—an approach that already distanced them from the strictly luxurious idiom of late Art Deco.

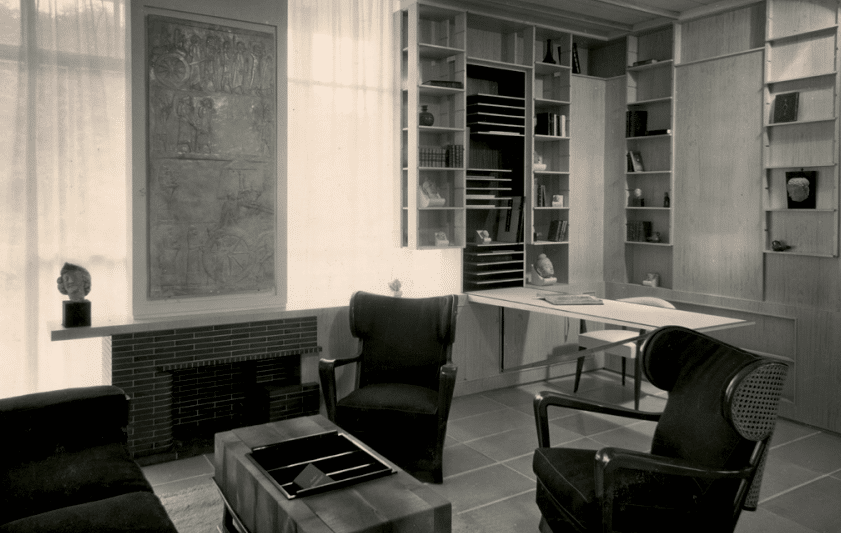

Picture of the Office of the archaeologist designed by Maxime Old at the 1937 Paris Exhibition. Note the desk in the back: it can also fold when needed. Keep it in mind when looking at the next pictures below. From the Maxime Old Archives, Paris, DR

Back in Paris from 1934, their work gained visibility through major exhibitions, culminating in the 1937 International Exhibition of Arts and Techniques in Modern Life in Paris, where they exhibited alongside Maxime Old in the Pied-à-terre of an archaeologist. Their smoking room concept (supported by illustrator André Marty) earned them a gold medal. Their presentation confirmed a shared ambition among this generation: to transform the decorative arts into a modern, human-centered discipline.

Oak drop-front desk by Janette Laverrière and Maurice Pré in the 1950s. The influence of their collaboration with Maxime Old is striking (folding, modular furniture). © La Maison Bananas

The war brought this partnership to an end. Maurice Pré and Janette Laverrière separated in 1946, leaving behind a compact but formative chapter in Pré’s career.