This article examines Bonnard’s role, situating “La Petite Blanchisseuse” as a hinge between painting and print, and explores how Nabis prints circulated via editions, posters, and the support of visionary dealers to reach new audiences. The BnF’s exhibition “Impressions nabies” in Paris, along with its remarkably rich online companion “L’estampe nabie”, were fundamental resources for this article. We are deeply grateful to institutions that share content of such quality with the world.

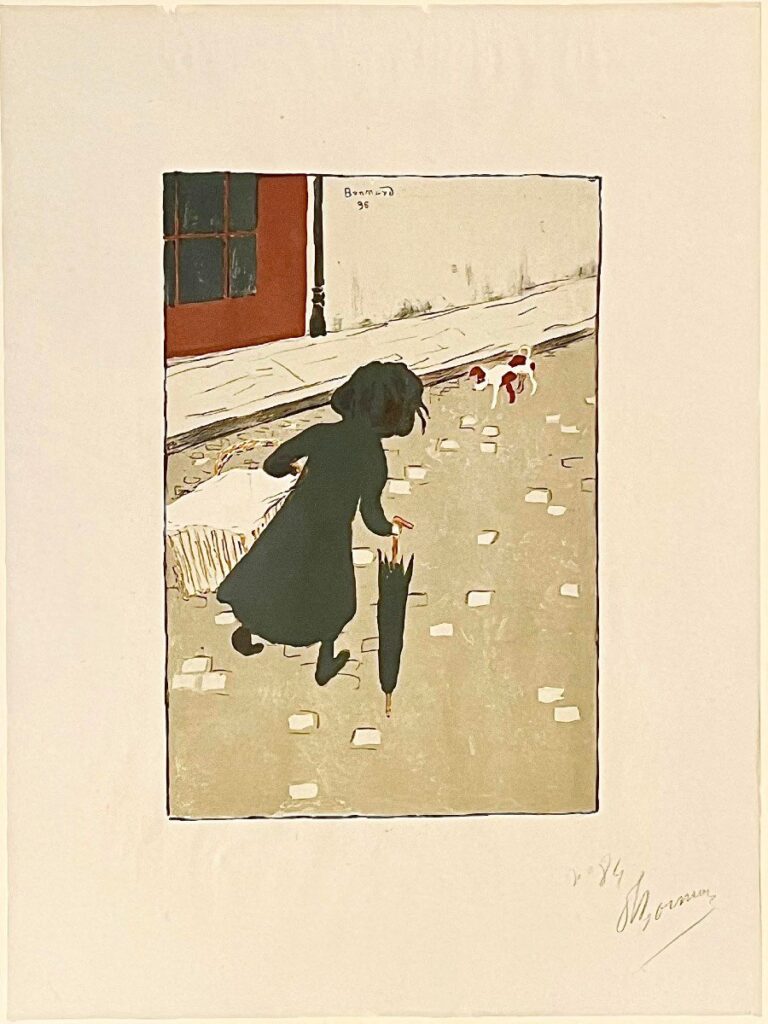

In 1895–96, Pierre Bonnard (1867-1947) created “La Petite Blanchisseuse” (“The Little Laundry Girl”), a color lithograph published by Ambroise Vollard as part of his “Album des Peintres-Graveurs”. This deceptively simple scene (in the center of the banner above)—a solitary young girl carrying a laundry basket down a flattened, planar street—embodies a crucial shift: the translation of intimate, quotidian life into a reproducible graphic medium.

Bonnard, like his fellow Nabis, saw in the estampe (print) a means to blur the boundary between high art and everyday experience. Through lithographs, woodcuts, illustrations, posters, and magazine graphics, the Nabis strove to fold art into life, offering aesthetic experience to a broader public rather than an elite few.

Pierre Bonnard and the Graphic Turn of the Nabis

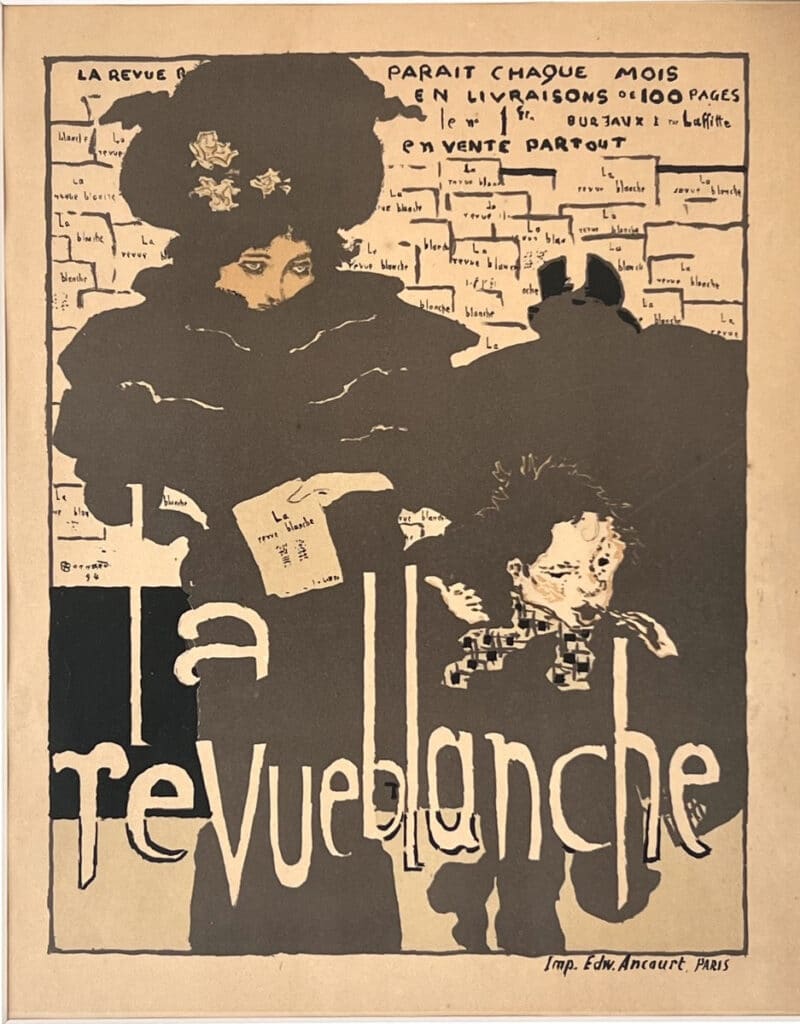

From the earliest days of the Nabi circle, Bonnard was drawn to graphic media. He and Édouard Vuillard (1868-1940) contributed to “La Revue Blanche” with frontispieces and vignettes, embedding art within a modern literary-public sphere. The name given to Bonnard within the group—“le Nabi très japonard”—signals his intense fascination with Japanese ukiyo-e, and the ways its flattened planes, bold outlines, and asymmetrical compositions reshaped his pictorial vocabulary.

When a major exhibition of Japanese prints opened at the École des Beaux-Arts in 1890, Bonnard and his contemporaries absorbed lessons in visual economy, cropping, and decorative flattening. You can see for yourself the variety of the exhibited prints thanks to the catalogue prefaced by Siegfried Bing.

Detail of a 1860 Japanese print by Utagawa Hiroshige, The Fan Room of the Gankirô Tea House in Yokohama. © Histoire de l’Asie

In “La Petite Blanchisseuse“, the laundress is silhouetted against pale paving, her form delineated sharply, the background abstracted to planes of gray, white, and subtle hues—features often ascribed to Japanese influence.

Other Nabis—Maurice Denis, Paul Sérusier, Ker-Xavier Roussel, Félix Vallotton, Paul Ranson, Henri-Gabriel Ibels—likewise experimented with lithography or woodcut, turning to printmaking to echo their belief that art should pervade daily life. Vallotton especially became renowned for wood engravings, and Ibels ventured into graphic journalism and poster art. Through prints, the Nabis could bridge the realms of book illustration, periodicals, decorative objects, and accessible visual culture.

La Petite Blanchisseuse by Bonnard: A Microcosm of Nabis Print Ambitions

Bonnard’s lithograph of the laundress is modest in size yet ambitious in conception. It was issued in an edition of approximately 100 copies (or fewer in some states) by Ambroise Vollard, part of his “Album des Peintres-Graveurs“, which gathered works by diverse artists as a curated portfolio. The print’s technique is a multicolor lithograph on fine China paper, executed with lithographic crayon. Though the subject is humble, the stylization is deliberate: perspective is flattened, forms are compressed, and architectural elements recede behind the figure. The dog at her feet echoes motifs of quiet domestic life, while the narrow street framing accentuates her path.

The Little Laundry Girl, a color lithograph by Pïerre Bonnard. Numbered 84 and signed in pencil at the lower right. Dated 1896. 34 x 45.5 cm. © Galerie A&G

What’s striking is that Bonnard chose a working subject—not a myth, not an allegory, but a laboring child in urban service. In doing so, he reflects the Nabis’ interest in bringing the poetic dignity of everyday life into visual discourse. Yet through the medium of editioned print, he simultaneously folds that dignity into reproducibility.

The image is both unique in aesthetic conception and democratized in circulation. Vollard priced the portfolio at 150 francs—and by reproducing such works, made them accessible (relatively speaking) to connoisseurs and collectors beyond the gallery context. In this dual stance, La Petite Blanchisseuse becomes emblematic of the Nabis’ ambition: art that moves from the studio into the reader’s hand, the wall, or the street.

Nabi Prints in the World of Publishing

One of the central outlets for Nabi’s graphic art was the domain of publishing—magazines, literary journals, and books. The arts and letters circles of fin-de-siècle Paris provided a ready forum. Bonnard and Vuillard’s involvement in “La Revue Blanche“ is well documented: they produced decorative elements, title pages, and illustrations that merged text and image, giving rise to an art-inflected periodical form.

The “La Revue Blanche” 1894 poster by Pierre Bonnard was published as a lithograph on vellum paper in September 1896 by “Les Maîtres de l’Affiche”. © 1900 by SP

Beyond “La Revue Blanche“, Nabis woodcuts and lithographs appeared in high-end bibliophilic editions, poetry collections, art journals, music theory books, and portfolios. The Nabis explored the entire spectrum: from stand-alone prints and albums to decorative programs and book illustrations.

In these printed forms, art ceases to be a remote spectacle and becomes a companion to daily reading. The reproduction potential of the estampe means that a work’s aesthetic value coexists with its function as an adjunct to literature or commentary. Illustrations in books turn pages into miniature galleries; decorative vignettes become motifs of visual identity for publications.

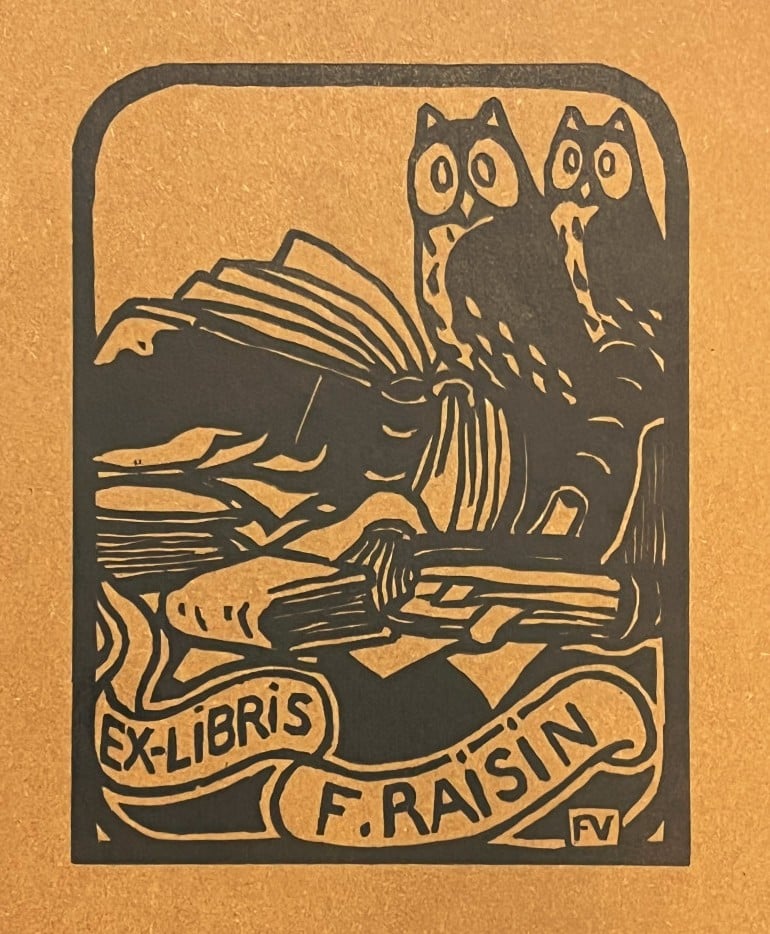

Félix Vallotton created this ex-libris with owls and books for Frédéric Raisin. Vallotton became a master of black-and-white woodcut prints. © Galerie Sophie Marcellin

For many readers, encountering a Bonnard- or Denis-designed motif in a journal served as their most immediate contact with modern art. In this sense, the Nabis democratized art consumption not by renouncing complexity but by channeling subtle artistic interventions through everyday media.

Affiches, Performances, and the Stage

The graphic ambitions of the Nabis extended beyond printed text into the realm of spectacle: posters, theater programs, playbills, and visual publicity. At the turn of the century, the poster was a vehicle of mass visual culture. Bonnard himself produced posters (such as for France-Champagne) that combined decorative flair with typographic inventiveness. Others—Henri-Gabriel Ibels, especially—came from the world of journalism and spectacle, producing program covers and posters for cabarets and theatrical events.

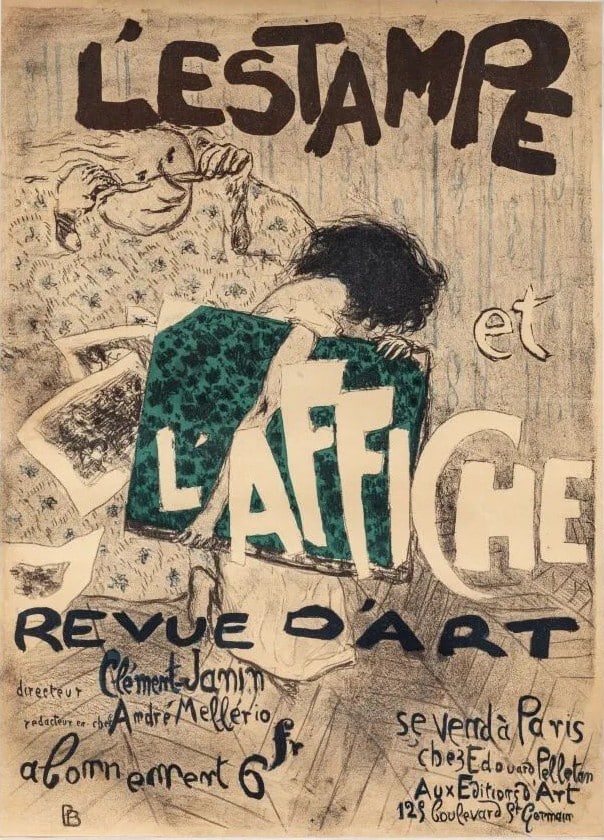

Original 1897 promotional poster by Pierre Bonnard for the art magazine “L’Estampe et l’Affiche”. 83 x 60 cm with old linen backing. © Thierry Neveux

The connection is deeper: some Nabis were regulars at Parisian cabarets (“Le Chat Noir”, for example), where shadow plays using zinc cutouts borrowed directly from print and silhouette traditions. Bonnard and his friends attended such performances and absorbed their visual logic—flat figures, negative space, dramatic silhouette.

The theatrical printing of programs and posters created a bridge between the visual arts and performance, turning theatergoers into potential art audiences. In this cross-pollination, a lithograph might become a poster, a program cover, or an illustration, all participating in the visual circulation of Nabi aesthetics.

Thus, the estampe becomes not just a private image but a civic sign, present in public spaces—from walls to sidewalks to theater doors—effectively integrating art into the civic fabric.

The Role of Innovative Art Dealers: Ambroise Vollard and the Ecosystem

No conversation about the circulation and accessibility of Nabis prints can omit the crucial role of art dealers and print publishers. Among them, Ambroise Vollard stands paramount. He was a pioneer in commissioning original prints by avant-garde painters, organizing portfolios (such as the “Album des Peintres-Graveurs“), and marketing their works to a growing bourgeois and international clientele. In the case of “The Little Laundry Girl”, the publisher was explicitly Vollard. Vollard’s model was to promote limited editions, artistic quality, and prestige, thereby making modern prints valuable yet attainable.

However, Vollard was not the only gallery supporting the avant-garde. Several dealers saw it as their mission to promote modern art, among them:

- Le Barc de Boutteville, a gallery that early on supported the Nabis (including exhibitions of Bonnard and contemporaries);

- Durand-Ruel, which staged Japanese print exhibitions and nurtured modern artists, placed Nabi prints alongside paintings;

- Bernheim-Jeune, after being a leading gallery for the Impressionists, organized exhibitions with the Nabis from 1900 on;

- The Natanson brothers (especially Thadée Natanson) had ties to “La Revue Blanche” and commissioned Bonnard’s work for their publication.

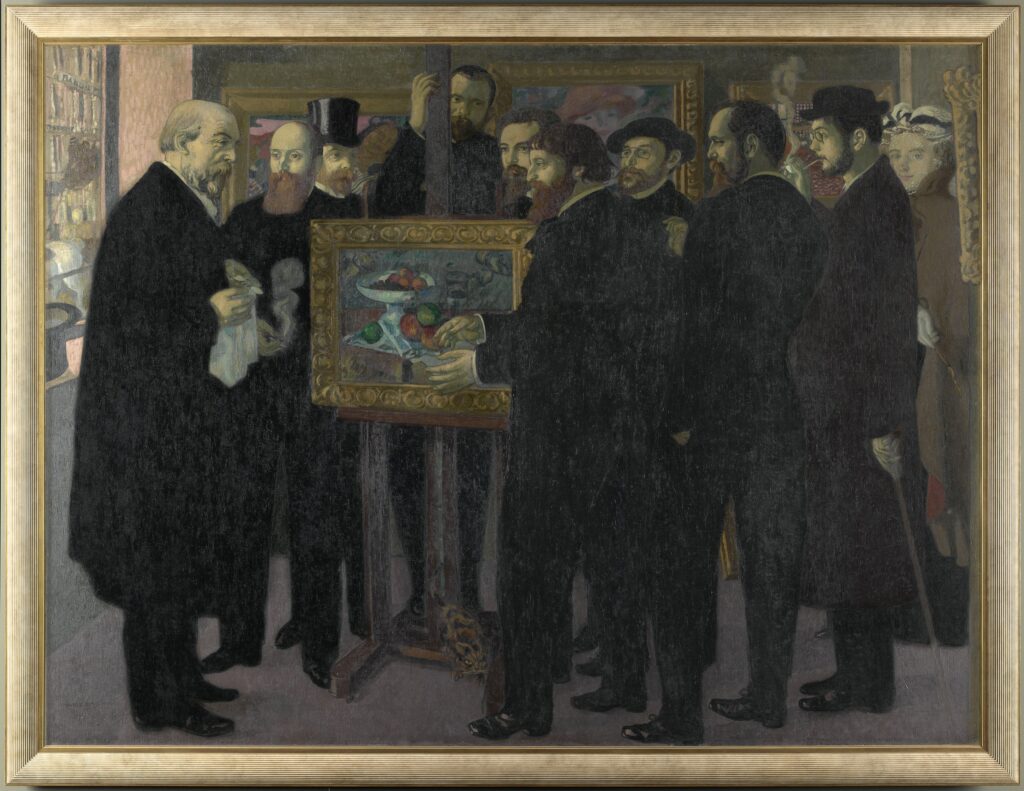

Homage to Cézanne, a painting by Maurice Denis in 1900. It takes place in Ambroise Vollard’s gallery. Vollard is behind the easel of Cézanne’s painting. Many Nabi painters are present: Paul Sérusier is talking to Odilon Redon. Also, Edouard Vuillard, Maurice Denis, Paul Ranson, Ker-Xavier Roussel, and Pierre Bonnard. © GrandPalaisRmn (musée d’Orsay) / Adrien Didierjean

In this ecosystem, Vollard’s role was central, not merely as a merchant, but as a cultural mediator: commissioning, promoting, and contextualizing prints as works of art, not cheap reproductions. His vision enabled prints by Bonnard, Vuillard, Denis, and their circle to reach beyond elite salons into the hands and homes of serious collectors and educated enthusiasts.

The Nabis Influences, Including the Pont-Aven Legacy

The Nabis did not emerge in isolation. Their shared belief that art should be woven into everyday life stemmed from deep collective influences and the model of Pont-Aven, where Paul Gauguin and Émile Bernard had pioneered synthetism—the union of idea, color, and line to express inner emotion rather than imitation. Paul Sérusier, who studied under Gauguin, became the link between Pont-Aven and the young Parisian painters. His “Talisman” (1888), painted under Gauguin’s direction, was adopted by his friends as a visual manifesto: simplified forms, flat color, and harmony over naturalism.

From this foundation grew a brotherhood—Sérusier, Bonnard, Vuillard, Denis, Vallotton, Roussel, Ranson, Ibels, Maillol—each asserting individuality while pursuing a shared vision of art’s spiritual and decorative role. They called themselves “Nabis,” or “prophets,” positioning their work as a revelation of beauty accessible to all. What united them was not a fixed style but an ethos: to dissolve barriers between art and life.

Beyond Paul Gauguin and Émile Bernard, one should not overlook Paul Cézanne’s indirect influence on the Nabis. As noted earlier, Maurice Denis—the theorist and spokesperson of the group—expressed his fascination for the Master of Aix-en-Provence in his 1900 painting “Homage to Cézanne”. Accompanied by Ker-Xavier Roussel, Denis met Cézanne in 1906, just nine months before the master’s death, immortalizing the encounter in “The Visit to Cézanne”. In his September 1907 article for “L’Occident”, Denis observed how difficult it was to define Cézanne’s style. The only broad agreement, he noted, was that Cézanne deeply influenced the younger generation and stood as a representative of classicism—however elusive a notion classicism may be.

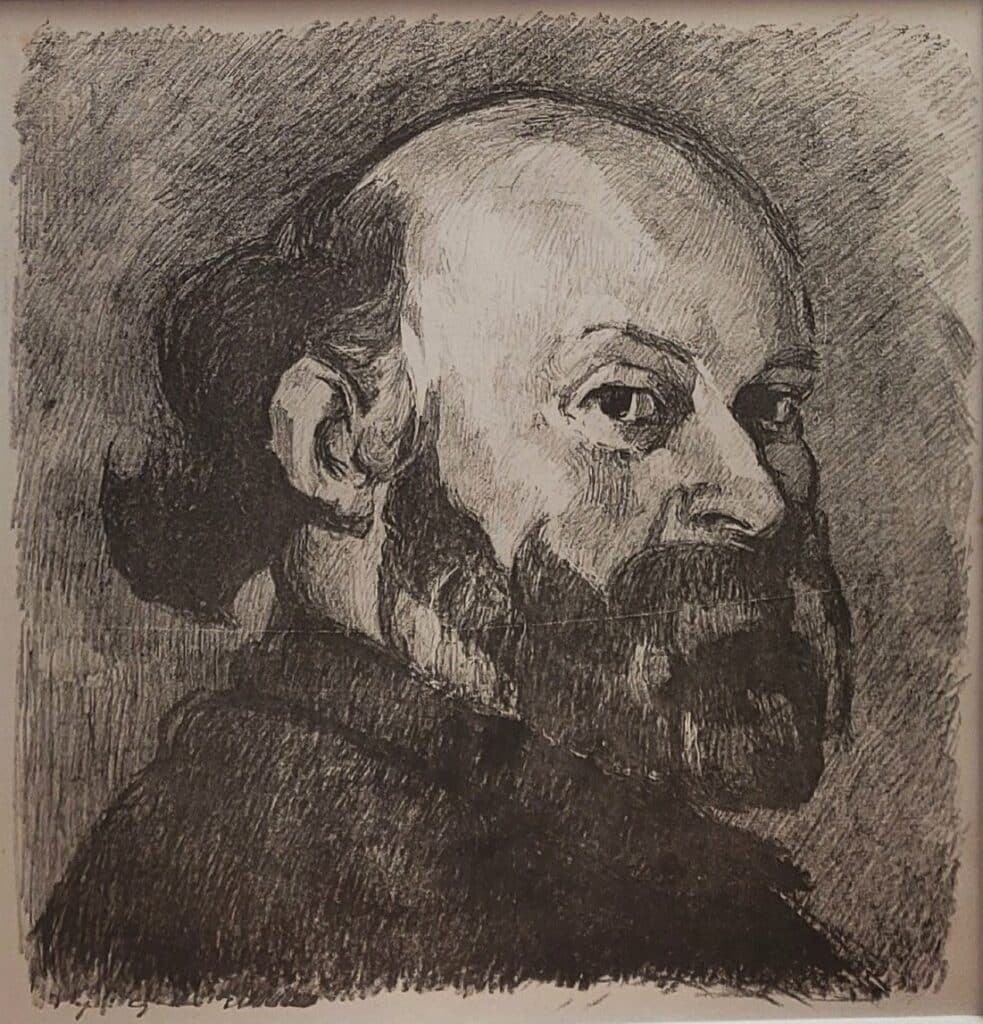

Portrait of Paul Cézanne by Édouard Vuillard. A lithograph on vellum published in 1914 by Bernheim-Jeune for their “Cézanne” album. © Galerie Portalis Aix

Unlike their Pont-Aven mentors, the Nabis turned decisively toward reproducible media. They brought the synthetist aesthetic into lithography, woodcut, and illustration, translating painterly ideals into forms that could circulate widely. Bonnard’s luminous contours, Vuillard’s intimate interiors, Denis’s symbolic devotion, Vallotton’s incisive woodcuts—all show how individual language could serve a collective philosophy.

Collaboration defined their modernity. The Nabis worked across books, posters, paravents, and theatrical prints, transforming daily objects and printed pages into sites of art. Through these shared ventures, they realized what Pont-Aven had only suggested: an art simultaneously spiritual and democratic, at home in both the gallery and the street. By fusing Gauguin’s decorative symbolism with the new technologies of print, the Nabis reinvented modern art as a collective experiment—an art of vision, intimacy, and accessibility.

Conclusion

By leveraging print media, the Nabis expanded the domain of art from salons to streets, magazines, books, and public walls. Bonnard’s La Petite Blanchisseuse stands as a fulcrum in this project: it is at once a carefully composed artwork and a reproducible object that participates in mass visual circulation. Over time, prints by Bonnard, Vuillard, Denis, Sérusier, Roussel, Maillol, Ranson, Vallotton, and Ibels turned into cultural signifiers in journals, decorative arts, and public advertising.

The consequences are profound: art is not locked behind elite barriers but enters the sphere of lived experience. By choosing the print as their medium, the Nabis enacted a democratic philosophy of visual culture. Their work prefigures later modernist efforts to integrate typography and design, to erase the boundary between fine and applied arts, and to make the aesthetic dimension part of urban life.

You May Like

19th-Century Prints | Pierre Bonnard | Les Maîtres de l’Affiche | Art Nouveau (in Fine Art)