With this guide about René Lalique’s glass artworks, we give you a thorough overview of his incredible portfolio (vases, mascots, lighting, tableware, and so much more), brushing over the evolution of his Art Deco style and techniques from the 1910s to the mid-1940s while keeping his inimitable personal touch. Discover what makes Lalique’s art eternal and instantly recognizable.

[René Lalique] maintained, in his noble independence, a place at the avant-garde as a maverick; often imitated, often slavishly copied, but always unmatched, he is one of those whose name future generations will repeat with reverence, as that of one of the masters of French art at the beginning of the 20th century.

— Gabriel Henriot (in 1927)

Table of Contents

- Lalique’s Poetic Universe and Techniques (His Inspiration / The Lalique Look / Lalique’s Technical Expertise)

- Lalique x Coty: Where Perfume Bottles Became Art

- Vases, Lalique’s Biggest Pride

- Bowls and Tableware

- Radiator Caps and Paperweights

- Lighting

- Lalique’s Architectural Works

- Glass Jewels

- Other Decorative Glass Objects

- Timeline of René Lalique

- Conclusion

René Lalique (1860-1945) was a major star of glass art during his lifetime. His creativity was expressed in poetic inventiveness as much as in endless experimentation, and labor fueled his whole career. He was consecrated as a jeweler in a striking Art Nouveau style during the 1900 exhibition. Yet, this relentless innovator had already created his first glass vase in 1898, and in 1912, he stopped making jewelry.

As mentioned in another one of our articles, the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts was a crowning achievement for Lalique (Lalique’s creations are present in around 20 spots in this fair). In addition, as early as 1933, the Musée des Arts Décoratifs honored him with a retrospective exhibition at the Pavillon de Marsan. In 1938, Paris presented King George VI and Queen Elizabeth of England with a table set crafted by Lalique, a testament to the artist’s prestigious status.

The dining room of the Lalique Pavilion at the 1925 Exhibition of Decorative Arts in Paris. A photo from albums by the designer Maurice Dufrene. © Alexia Say

Given his dazzling reputation between the two World Wars, we chose to draw upon what was written in the press at the height of his career. In January 1927, Gabriel Henriot expressed his admiration for Lalique’s work in one of the leading French interior design magazines of the time, Mobilier et décoration.

We have therefore incorporated a few excerpts from this article (quoted without further attribution) into each section dedicated to the various types of objects created by Lalique. Concerning these pieces, the 1932 Catalog of René Lalique’s Glassworks serves as an important and publicly accessible reference.

While this article does not delve into René Lalique’s early career or industrial endeavors, a brief chronology of the illustrious artist is included in the conclusion to provide a comprehensive overview of his career.

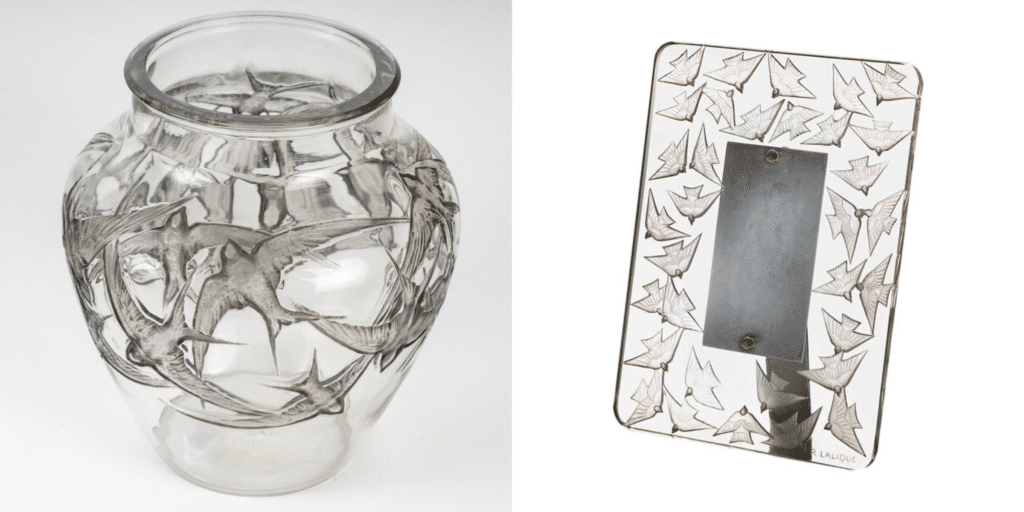

A testament to the evolution of Lalique’s style: swallows, created just seven years apart. In 1919, with the vase on the left, Art Nouveau is visible in the detailed curves of the birds. By 1926, with the frame on the right, the swallows are rendered in a geometric, stylized form. © Alexia Say

Lalique’s Poetic Universe and Techniques

His Inspiration

“Wide-eyed and receptive, everything impresses him, everything moves him: wild plants or seaweed, birds of our skies or fish from distant oceans, human figures or chimerical creatures—each piece, born of his mind and hands, is a poem of perfect craftsmanship.”

Outside of nature, women are another major source of inspiration. Often a mythological or magical woman, mysterious and sensual, whose representation was probably nourished by Symbolism, the artistic movement that flourished in the late 19th century.

Bacchantes is amongst Lalique’s most famous vases. Created in 1927, it boasts Lalique’s signature opalescence, mystical women, and full-of-life carving. © BG Arts

The Lalique Look

Lalique’s glasswork gives this poetic world an ethereal presence. Whereas Art Nouveau explored multi-layered glass, Lalique does magic with transparency and reliefs. Light can play in the different volumes, coming out bright or softened.

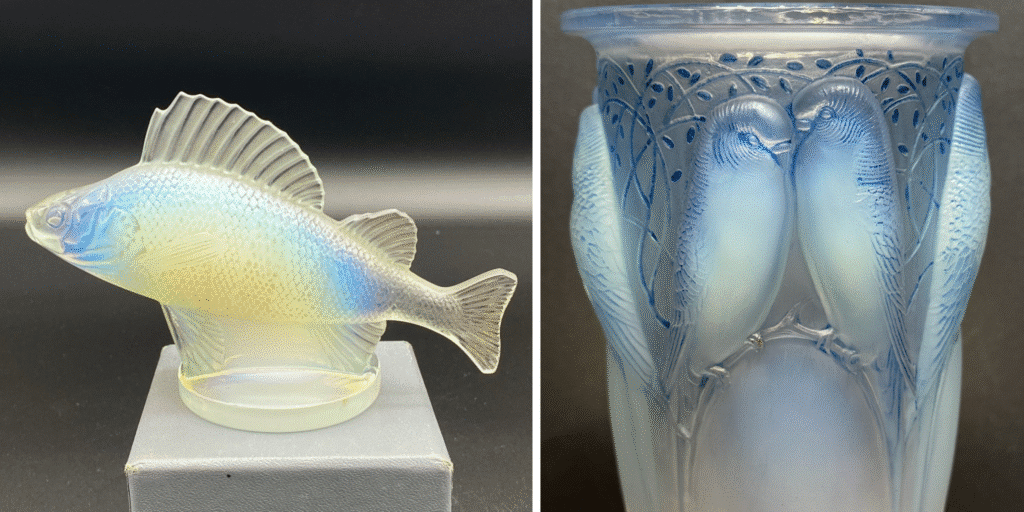

With Lalique’s imagination, glass can mimic water in all its forms. His work has the freshness and twists of running water, or looks like an ice sculpture (when glossy), the opalescence or satin finish settling like a veil of mist or morning dew.

Across the full range of objects Lalique created, clear (uncolored) glass remains the most prevalent. However, the palette he employed was remarkably wide, spanning virtually every shade of the rainbow. Opalescence offered yet another means of introducing color—ranging from milky white to iridescent blue—while also lending the pieces a unique inner glow. It cannot be overstated: opalescence is one of René Lalique’s most distinctive trademarks.

Two Lalique models with opalescence: a 1929 Perche mascot and a 1924 Ceylan vase with parakeets. © Mezza-notte

Patination is also skillfully employed by Lalique to enhance ornamental details or evoke an antique appearance, often with a touch of melancholia. The patinas typically appear in shades of grey, sepia, blue, or green, and occasionally in white when applied to colored glass.

Enameling, though rarer, is used in a distinctly modern way—not to depict entire scenes, but to introduce vivid accents on clear or colorless glass. Naturally, Lalique was already well acquainted with enamels from his earlier career as a jeweler, long before he turned to glass.

Lalique’s Technical Expertise

Despite the exceptional value of the unique pieces made with the lost wax technique, the most compelling aspect of Lalique’s craftsmanship is his capacity to produce highly beautiful pieces in series with an industrial process. According to Maximilien Gauthier in a 1926 article, René Lalique confessed that:”[…] none [of the lost-wax artworks…] has brought him as much personal joy as the humblest of his inexpensive items, routinely manufactured in his Alsace workshops.”

His abundant creativity extended beyond the artistic realm to encompass technical inventions that brought his designs to life. Between 1909 and 1936, René Lalique filed 15 patents related to glass or concerning the installation and lighting of his decorative elements.

The Riquewihr table glass service, created in 1925 by René Lalique, was discontinued after 1947. The glasses employ the two principal glassmaking techniques outlined below: molded-blown for the bowl, and molded-pressed for the stem. © Verre et Cristal – Gilbert Pautot

Blown Glass in a Mold

The parison held in a crucible was blown into a metallic mold opening in four pieces. With colored glass, a second layer of parison could be added inside the first one after just a few seconds, creating a subtle sense of depth.

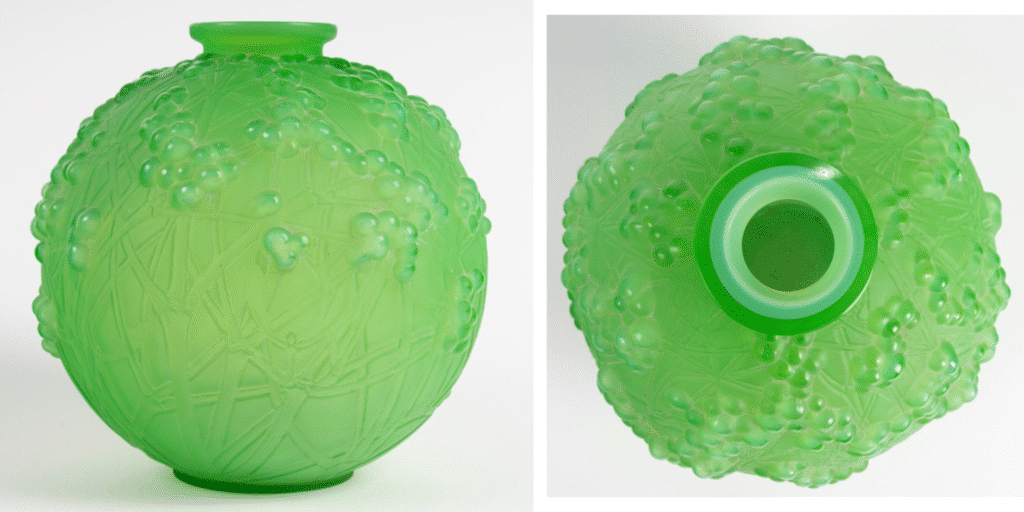

The two layers of jade green and peppermint create a unique iridescence on the mistletoe berries of this Druide vase, designed in 1924. © BG Arts

In 1928, René Chavance describes how the blowing is mechanized with compressed air: “[René Lalique] resolutely uses compressed-air blowing, supplied to each team through a pipe system arranged in a circle around the furnaces. This spares the worker from strenuous and unhealthy labor, while also delivering reliable results when skillfully handled.”

Mold-Pressed Glass

Lalique masterminded this technique so well that, as early as 1909, his first patent related to glass enabled him to create perfume bottles on a larger scale despite the initial difficulty of duplication due to the narrow cap opening. Using this mold technique made it possible to give the bottles finer details than with blown glass.

An original and charming way to use it was to have two distinct motifs, one inside and one outside a bottle. That was the case with Lunaria. For Pavots and Œillets, the shape of the related flowers was molded inside, whereas the outside was round and smooth.

In this 1920 Lalique Mûres inkwell, the intaglio effect with the molten-pressed process used for the bottom is superb. The top is smooth and glossy. © Verre et Cristal – Gilbert Pautot

Lost Wax

Even the old technique of lost wax—which he first used as a jeweler—was given a modern twist with compressed-air blowing for the most spectacular results. The prestige of these pieces is related to their rarity, made for special occasions (exhibition, present, commission). They don’t carry mold marks.

Lalique x Coty: Where Perfume Bottles Became Art

“These delicate trinkets are, in fact, almost like pieces of jewelry. He began with perfume bottles, which launched the products of our great perfumers around the world—more effectively than any advertisement could.[…]

The beauty of the material, the originality of the form, and the perfection of the decoration are the hallmarks of each piece. Yet whatever their appearance, one can see that the same refined, logical, and confident taste presided over their creation.”

An iconic tiara perfume bottle by Lalique with a cap unfolding like a halo. This model, ornated with apple blossoms covered in a sepia patination, was created in 1919. © BG Arts

Though praised for their beauty, the bottles’ resounding success owed much to their affordability, made possible by Lalique’s technological innovations (his first bottle patent was filed in 1909), which enabled mass production. Nearly 300 bottle models were designed for perfume houses, and 80 were commercialized directly by Lalique (in addition to those included in toilet sets).

Lalique started his first perfume collaboration with François Coty in 1907. Interestingly, some bottles were designed with a specific perfume in mind, while others were used interchangeably for several fragrances. Sometimes the perfume name is written in full on the bottle, making things crystal clear (pun intended).

A bottle created for Coty’s perfume “Ambre Antique” in 1910. Blown molded glass with sepia patina. © Galerie Achille Antiquités

Other French perfume makers (Worth, Molinard, Houbigant, Roger & Gallet, d’Orsay, Volnay, Forvil, Lucien Lelong) soon followed suit in working with Lalique, a clear sign that he was unmatched by other glass manufacturers.

Vases, Lalique’s Biggest Pride

Lalique was the most prolific in this category. In the 1920s, Lalique created over 200 models. With the vases, he was able to use all the possible shapes, textures, and colors. His pieces are a tour de force for display rather than for flowers, especially as most of them are less than 25 cm high.

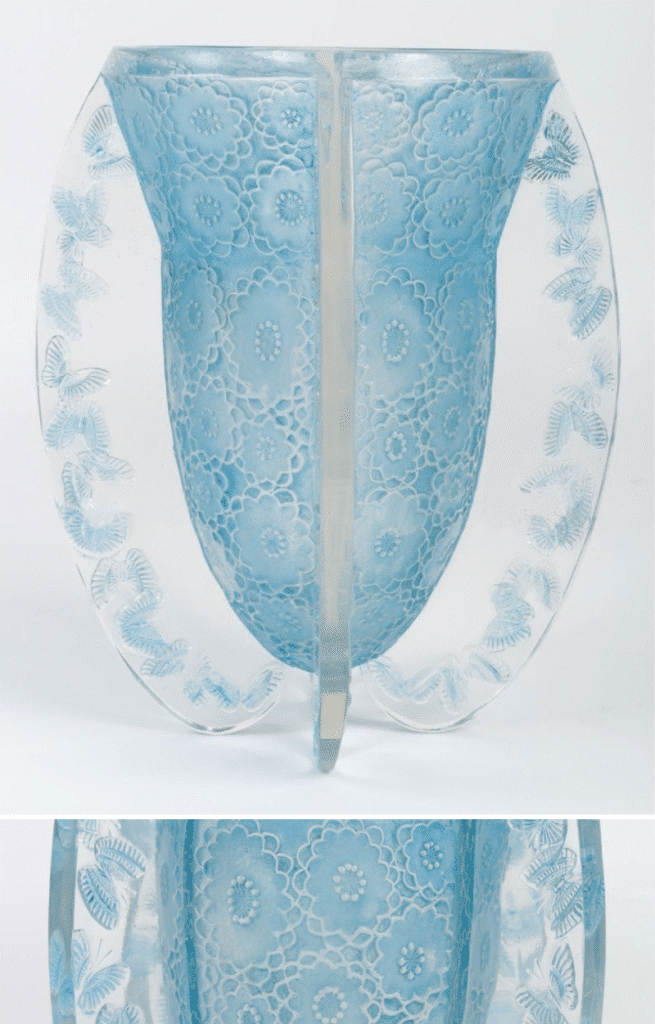

This Papillons (butterflies) vase by Lalique created in 1936 has a blue patination. The shape is unconventional, ovoid with four fins. © Alexia Say

Many models are in opalescent or white glass. However, some are made of colored glass (such as Serpent, Druides, Espalion, and Perruches). A sepia or grey patination is among the big classics, though some blue or lavender patination comes up. Some include enameled high reliefs (e.g. Tourbillons) or patterns (e.g. Baies).

This 1926 Lalique vase “Tourbillons” showcases powerful geometrization. The high reliefs are enameled in black. Suzanne Lalique (René’s daughter) designed it. © BG Arts

Bowls and Tableware

Some bowls are meant to be purely ornamental and echo the stylistic traits of the vases. Shapewise, most of them are fully rounded, though their depth varies, while a minority feature a flat rim (e.g. Phalènes, Éléphants).

Fish and seaweed on this 1930 Lalique Anvers bowl in sapphire blue. © BG Arts

Some bowls belong to the tableware category, typically used to serve salad or fruit desserts. In this case, they lean towards more simplicity, and some are decorated with salad leaves (chicory, dandelions).

Tableware made it possible to open Lalique’s audience to a wider public. The Lalique dining room at the 1925 exhibition was consistent with this popular success. “It is for [the broad masses] that he produces, in series, at his Alsace factory, glassware whose beauty rivals that of unique pieces—the precious objects one finds in collectors’ display cases.”

Radiator Caps and Paperweights

In addition to their artistry, radiator caps carry the nostalgic appeal of a bygone function. Sitting proudly atop car hoods at the most forward end of the vehicle, they were car mascots too, similar to figureheads for ships. Today, they are the living symbols of the glamorous cars developed at the beginning of the automobile civilization.

How ingenious of car owners to repurpose Lalique paperweights as hood ornaments—a witty way they devised to personalize their vehicles. These mascots were elegant status symbols, too. Lalique even equipped some personal vehicles of the British royal family. Motifs related to speed and power were particularly coveted (birds and animals, an archer). Saint Christophe, a protective figure, was also an option.

Based on Lalique’s spontaneous and unexpected success for radiator caps, Citroën ordered a dedicated model for the 5 CV in 1925, hence the famous 5 Chevaux. This inspired the creation of more models designed solely as car mascots: Victoire, Vitesse (also made as a figurine), Epsom, Petite Libellule, and Comète.

When Citroën ordered a mascot for their 5CV in 1925, playing with the car’s name, Lalique created 5 stacked horses. © BG Arts

All of them were available in white glass. Only a few in colored glass: Vitesse, Tête de paon, Sanglier, Grenouille, Coq Houdan, Coq Nain, Chrysis, Perche, Tête d’Épervier. The last two also had an opalescent version (cf. a picture of an opalescent Perche higher in the article).

However, white glass didn’t necessarily result in a white-looking mascot. Once again, Lalique’s brilliance shone through: he had patented a lighting system mounted beneath the mascot, where a simple colored glass slide—connected to a dynamo—caused the mascot to glow with varying intensity depending on the car’s speed.

Lighting

René Lalique experimented with electricity early on, first for glass panels in 1902, driven by both aesthetic and business potential. Early in the First World War, he created table lamps with glass shades set atop wrought iron stands.

He moved to ceiling lamps, typically designed as large bowls suspended by chains or cords. When the motifs increase the glass thickness, they work as lenses, intensifying the light. The bowl-like shape explains why similar designs appear on both tableware and lighting pieces (such as Coquilles).

A two-tier Perles chandelier created in 1931 by René Lalique. A perfect combination of geometry and classicism. © Mezza-notte

Wall lights were also designed, sometimes to complement a chandelier. Opposite to intense light, some night lamps were made from Lalique’s iconic tiara perfume bottle (see pictures higher in the article). Candlestick models are also numerous, often associated with tableware.

Lalique’s Architectural Works

Lalique’s monumental glasswork (such as wall panels, doors, or even tables) may have surprised his audience during the 1925 exhibition. In fact, he had experimented with panels for doors in his house in Cours-la-Reine in 1902, before he launched a commercial glass product line. Such panels leverage low reliefs on a large flat surface. Due to the interplay of light, one cannot help but think of the old tradition of stained glass—yet here it was cleverly subverted, with neither colored glass nor lead.

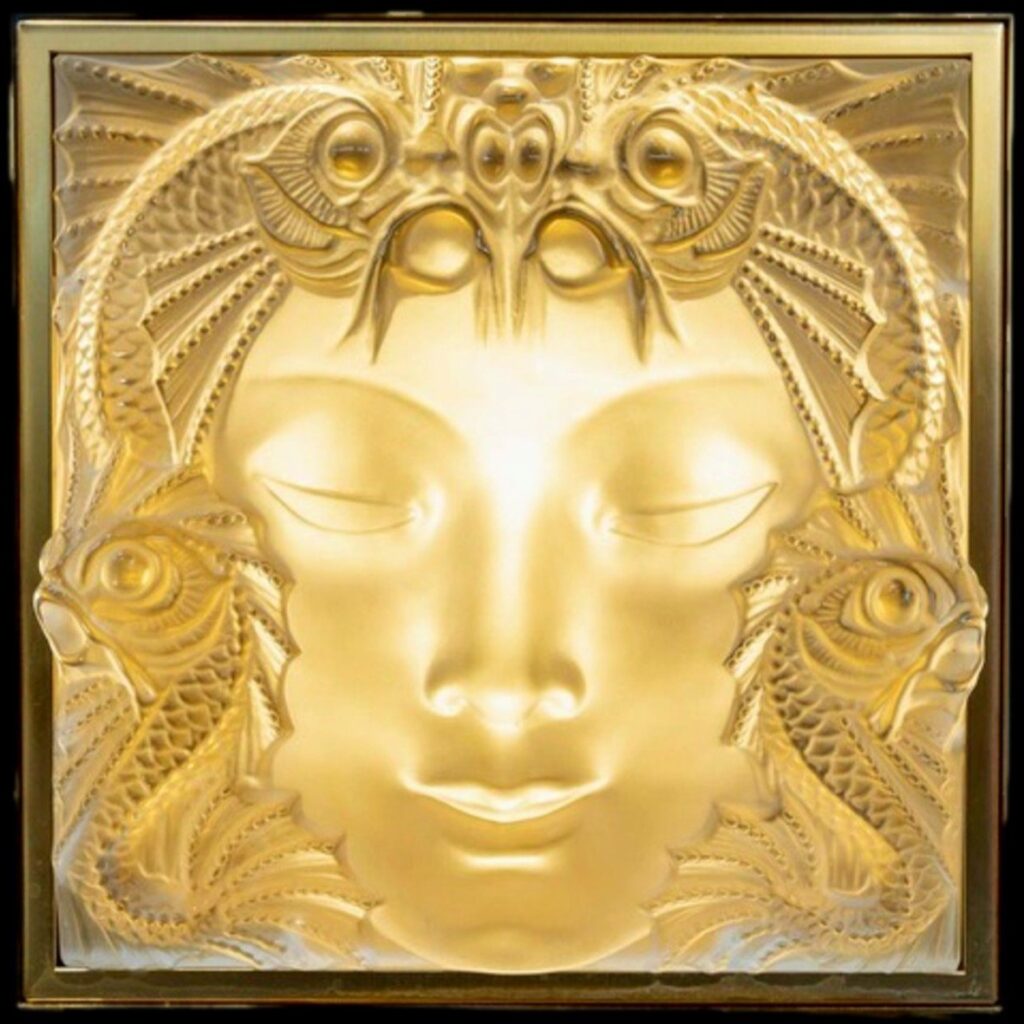

The Woman’s Mask, ornamented with fish and originally created by René Lalique for the Champs-Elysées fountain, was incorporated in several other Lalique artworks. © Alexia Say

When he decorated stores (for instance, Coty in New York in 1912, Worth in Cannes, or Maples in London) or homes (his own, Jacques Doucet in 1912 or Prince Asaka in 1932), ensembles were usually made of doors, panels, lighting, mirrors (and even tapestries), sometimes fountains. Lalique is also renowned for his contribution to the decoration of ocean liners and trains.

Glass Jewels

Yes, this part refers to glass jewels, not those he created during his first career (stopped in 1912) as a jeweler, where goldsmithing and stones or enamels were involved. This new generation of jewels was seen as costume jewelry, decorative but not precious, and therefore affordable.

A sample of Lalique’s glass jewels: 1913 pink brooch, 1919 green cross pendant, 1928 blue bracelet. They all carry a white patina. © BG Arts

These molt-glass jewels (mostly necklaces, pendants, bracelets, and brooches) have simple settings so that glass truly is the center of attention. Silk cords, elastics, or a brass mount keep it together. They are frequently colorful.

Other Decorative Glass Objects

With such a vivid imagination, Lalique had no trouble designing for nearly any other area of the decorative arts: mirrors, boxes, clocks…

In addition to functional objects, figurines were also created, some of which had a paperweight equivalent. The woman is the primary inspiration for the statuettes, as an allegory of beauty and vitality.

On this rare 1910 black glass box by René Lalique, the rooster and motifs have a white patination. © BG Arts

Timeline of René Lalique

A mermaid from a 1932 Calypso bowl by René Lalique. Clear glass with a blue-grey patina. © BG Arts

- 1860: René Lalique was born on April 6 in Aÿ (Champagne).

- 1876-1880: Lalique is an apprentice jeweller, takes classes at the School of Decorative Arts in Paris, and trains at Sydenham Art College in London for two years.

- 1880-1882: Freelance jewellery designer for Aucoc, Cartier, Boucheron, Hamelin…

- 1885: Took over a jeweler workshop in Paris, place Gaillon.

- 1887: Moved his workshop to 24 rue du Quatre-Septembre in Paris.

- 1889: Participated in the World Fair in Paris as an associate of Vever and Boucheron.

- 1890: Started his first experimentation on glass after moving to a new workshop at 20 rue Thérèse in Paris.

- 1895: Lalique exhibited his first glass artworks at the Salon.

- 1898: Bought a property in Clairefontaine (Yvelines). He had the space to set up a kind of mini glass factory with several ovens.

- 1900: Lalique is at his peak as a jeweller during the Paris World Fair.

- 1905: Opening of a store at 24 place Vendôme in Paris.

- 1907: Met François Coty, which led to the development of perfume bottles.

- 1909: Started to rent the Combs-la-Ville glassworks (about 30 km from Paris), which he bought in 1913.

- 1911: Lalique’s first exhibition devoted to glass.

- 1912: He stopped making jewelry (outside of glass jewels).

- 1921: Started La Verrerie d’Alsace glassworks in Wingen-sur-Moder.

- 1924-1935: Contributed to decorating ocean liners (De Grasse, Ile-de-France, Normandie) and the Côte d’Azur Pullman Express train.

- 1925: Lalique is omnipresent at the Paris World Fair with his pavilion, decorating other pavilions, and the emblematic main fountain.

- 1926: Saint-Nicaise church in Reims.

- 1932: Prince Asaka in Tokyo.

- 1933: Monographic exhibition at the Pavillon de Marsan.

- 1945: Lalique passed on May 1st in Paris.

These Cluny grey-patinated candlesticks, commercialized in 1944, are amongst the last models by René Lalique. © BG Arts

Conclusion

René Lalique’s artistic vision (enchanting natural motifs, an ethereal woman) and his technical inventiveness elevated everyday objects into exquisite, widely admired works of art. In addition to expressing his creativity, he skillfully adapted motifs across various products.

We focused on René Lalique, the founder of the Lalique enterprise and the creator of its most iconic and sought-after pieces. However, the story of Lalique is also one of a family business that evolved during René’s lifetime. His daughter Suzanne Lalique contributed several notable designs, such as Nanking, Tourbillons, and Nimroud. His son, Marc Lalique, became his associate in 1923 and took over after his father’s passing.

Under Marc’s leadership, the company transitioned entirely to crystal production, marking the end of its glassmaking era. In 1977, René’s granddaughter, Marie-Claude Lalique, became CEO and continued the family legacy. Since its acquisition by various corporations starting in 1994, Lalique has retained its iconic status and remains active, with its historic factory still operating in Wingen-sur-Moder.

####

The main sources of this article:

- Vane Percy, C. (1977). Lalique Verrier : Guide du Collectionneur. Edita-Denoël.

- Henriot, G. (1927, January). René Lalique. Mobilier et Décoration, 52–61.

- Gauthier, M. (1925, September). Le maître verrier René Lalique à l’Exposition des Arts Décoratifs. La Renaissance de l’art français et des industries de luxe, 414-419.

- Brumm, V. Brevets et innovation chez Lalique. Paper from the second international colloquium of the association Verre & Histoire held in 2009, “Innovations in glass making and their evolution from antiquity to the 21st century”.

- Press Kits of Musée Lalique.

####