Discover the exquisite tableware and furniture designed for serving hot chocolate in the 18th century, and explore the fascinating history behind its expansion in France. This cross-cultural journey traces the path of American cacao to the tables of France, passing through Spain and shaped by the artistic influence of Chinese and Japanese porcelain and decorative arts.

In Le Déjeuner, a 1739 painting by François Boucher, a chocolate pot, delicate cups, and a graceful cabaret table take center stage. Two elegantly dressed women—likely enjoying hot chocolate—share the moment with their children. At that time, King Louis XV, then in the prime of his life, was a known chocolate enthusiast. This exotic and luxurious drink had already conquered the courts of Europe, remaining a delicacy reserved for aristocrats and the elite.

A close-up of Le déjeuner by François Boucher in 1739. The two women seated at a cabaret table offer hot chocolate to their children. The waiter holds a chocolate pot. © RMN – Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Franck Raux

The Chocolate From Mexico: What Europe Learned From the Aztecs

Cacao and chocolate were brought back to Spain by conquistadors and missionaries in the 16th century. The Aztecs from Mexico introduced chocolate (xocoatl) to them, even though cocoa consumption is much older and originated with the Mayas in Guyana. For the Aztecs, the cocoa beans were a divine manifestation of Quetzalcóatl, the Feathered Serpent deity and bringer of knowledge. The beans were used as currency and for a drink served to the nobles.

A possible representation of a foaming cacao beverage with blossoms in the Zouche-Nuttal codex, a screenfold manuscript made in the Mixtec region (southern Mexico) between 1200-1521. It is served in a decorated tripod vessel. Public Domain The British Museum

In the Eight Decade of “De orbo novo decades” (relating the Spanish explorations in Central and South America) written by Peter Martyr d’Anghiera in 1525, the cacao tree and drink are described as such:

This tree [the cacao tree] produces fruits resembling a small almond. When fresh, they have a bitter taste and cannot be eaten, but from them is made the beverage of nobles and the wealthy. When dried, the seeds are ground into a flour, and, when the time comes for lunch or dinner, the servants take wine or water jugs, or handled cups, fill them with water, and add a quantity of this flour in proportion to the vessel’s size. They pour this mixture from one container to another, and churn it by raising their arms as high as they can, only to let it fall back down like rain falling from a rooftop. They repeat this process until a foam rises — and the more foam the drink has, the better it is said to be. Once the mixture has been agitated for about an hour, it is allowed to rest a little […].

The Aztecs mixed cocoa powder with chili pepper, corn semolina, and water. They frothed the drink by repeatedly pouring it between containers or by whisking it with a branch or a small mill (molinillo or swizzle stick). Their hot chocolate recipes and preparation methods significantly influenced the Spanish colonists.

An antique chocolate mug from Mexico, Guatemala, or Central America in the shape of a carved coconut mounted on sterling silver in the 18th or 19th century. © Eric Martin Antiquités

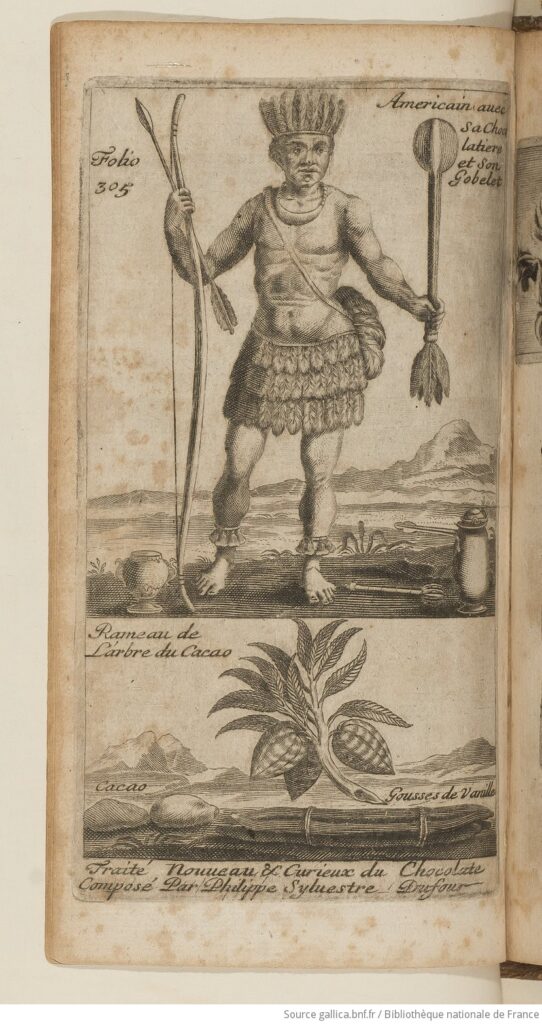

In 1685 when Sylvestre Dufour first published his “Traitez nouveaux & curieux du café, du thé et du chocolate” (New and Curious Treatises of Coffee, Tea, and Chocolate), a native American was represented with a chocolate pot, a whisk, and a goblet. However, their shapes were surely more attuned to the accessories used by the Spanish.

1685 French print of a Native American with a chocolate pot, a goblet, and a whisk. From “New and Curious Treatises of Coffee, Tea, and Chocolate” by Sylvestre Dufour. Public Domain BNF

The Chocolate Pots and Preparation of Hot Cocoa

The Chocolate Pot in the Preparation Process

In Europe, one particular accessory has remained inseparable from chocolate consumption for centuries: the chocolate pot (chocolatière in French) with a built-in slot in the lid to host a little whisk (moulinet or moussoir). In New Spain, the original pots to serve chocolate were in ceramic or copper.

In France, cacao was transformed into a chocolate paste. Chocolate drops or shavings were mixed with water (or milk as favored in Spain). Spices were first added, as done by the Aztecs. The Spanish enjoyed drinking it with honey or sugar, and vanilla, cinnamon, or clove.

A cavalier and a lady drinking hot chocolate, a 1695 print by Robert Bonnard (1652-1733). A serving lady is frothing the chocolate with a whisk in a chocolate pot. Public Domain BNF

The cocoa mixture was heated in a pot to melt. The challenge with chocolate was to keep it warm and as homogeneous as possible. A quintessential accessory for a smooth, creamy, and frothy chocolate drink was a wooden frother looking like a mill wheel with small fins. It was inserted vertically in the chocolate pot through a slot and rolled between the two hands, as the print above shows us.

Different Types of Antique Chocolate Pots

Hot chocolate could be prepared in different places. If the chocolate drink was prepared in a kitchen or outside (in a garden-party fashion), a copper chocolate pot with a flat bottom could sit on a stove or a braseiro. Then, it could be poured into a different stoneware, porcelain, or silver pitcher or even directly into a cup, then carried on a tray to whomever needed it.

An 18th-century copper chocolate pot.

With its flat bottom and long wrought-iron handle, it was perfectly suited for preparing hot chocolate on a stove. It still retains its original wooden molino for frothing the drink. © Boularand Antiquités

During the 18th century, a classic chocolate pot was round-bellied and three-legged in silver (potentially leaving some space below for a small warmer), with a wood or ivory handle perpendicular to the spout, and a removable finial to conceal the opening through which the frother passed. This model didn’t change much across that century; only the ornaments would vary from Rococo to Neoclassicism, if that. The elegance and refinement of such pieces remind us that drinking chocolate was once a privilege reserved for the few.

A silver French Rococo chocolate pot made in 1757-1758 by Charles Spire, a a master silversmith in Paris. It boasts typical rocaille ornaments and an ebony handle. © Galerie Verrier

Some chocolate pots were made of porcelain and could be part of larger hot drink services—sets that included cups and saucers, a milk pitcher, a sugar bowl (sucrier), and slop bowls, used for serving tea, coffee, or chocolate. Such a set was called a déjeuner (like the first meal of the day, a favored time for enjoying these exotic beverages); when accompanied by a tray, it was known as a cabaret (see the final section of this article for more on cabarets). When all the pieces were housed in a fitted box, the ensemble was referred to as a nécessaire.

The Meissen porcelain pot shown below likely belonged to such a set. Its shape closely resembles the one included in the gift made in 1737 by King Augustus III of Poland to Queen Marie Leszczyńska. However, its decoration—featuring cornflowers—places it in the late 18th century.

A late 18th-century Meissen porcelain chocolate pot with cornflowers. © Farella Frank Antiques

Jícara and Mancerina: The Original Spanish Chocolate Cup and Saucer Designs

Regarding the cups and saucers, before moving our interest to France, let’s focus on the cradle of chocolate consumption in Europe: Spain. The 18th-century Spanish kitchen tiling below displays, with a good dose of humor, the serving of hot chocolate with turrones. One chocolate cup is falling, and a few others are spilling. Drinking hot chocolate was no small risk, especially considering the threat of stubborn stains on fine silk and other luxurious fabrics.

Serving hot chocolate and turrones in 18th-century Spain. Ceramic polychrome tiling for a kitchen at the Museo Nacional de Cerámica y Artes Suntuarias “González Martí”.

The typical Spanish cup is named jícara, a term coming from the Aztec word xicalli, originally a vessel made of a half gourd used for drinking. It was first coined in Spanish in 1560 by Francisco Cervantes de Salazar in his “Chronicle of New Spain”. However, the shape of the jícara was marked by another exotic drink and culture for Europeans: the Chinese porcelain teacup. At first, such a cup had no handle similar to a goblet. The two handles, as shown in the example below, offer added stability—a particularly useful feature when drinking chocolate.

An antique chocolate cup in blue and white porcelain of the Kangxi period (1661-1722). With two loop handles. It originally had a lid. © Menken Works of Art

Precautions with chocolate went even further when it comes to influencing design. A special extra-large saucer, a mancerina, was created in New Spain in the 17th century. Its name stems from the First Marquis of Mancera, 15th Viceroy of Peru from 1639 to 1648. Mancerinas usually are very ornate with nature-inspired shapes: a ribbed scallop, a dove, or a tendril, for instance.

Outside of its size and shape, another specificity of a mancerina is the cupholder or ‘chocolate stand’. The saucer catches spilled liquid and helps the drinker avoid burning their fingers on a hot cup. It also serves as a small tray to hold pastries. The stand prevents the cup from tipping over.

A mancerina chocolate saucer in Famille Rose porcelain. Qianlong period circa 1770. Diameter of 21.6 cm. © Menken Works of Art

Mancerinas were first crafted in silver in colonial Mexico or Peru, and later produced in ceramics—typically earthenware from Alcora in Spain or export porcelain from China.

From the Royals to the Bourgeoisie, Hot Chocolate Became a Fashionable Drink

How It Spread From Spain to France

Chocolate reached European shores via Spain in the 16th century. In France, it made its royal debut when King Louis XIII married Anne of Austria—a Spanish infanta—in 1615. Along with her entourage of ladies-in-waiting, she brought chocolate to the French court.

Ironically, it was not Anne who popularized the drink, but rather Cardinal Richelieu—despite his deep suspicion of Spain and his strained relationship with the queen. Influenced by his elder brother, who had a strong taste for chocolate and used it medicinally “pour ses humeurs spleeniques” (for his melancholic humors), Richelieu became one of its early French enthusiasts.

History repeated itself when the next French queen, Maria Theresa of Spain, married Louis XIV in 1660. Like her predecessor, she was known for her deep love of chocolate—and of the king. Some malicious tongues could have suggested, however, that the chocolate comforted her more reliably than her husband, whose affections often lay elsewhere.

An oil painting depicting chocolate time during the early 18th century. A woman drinks chocolate offered by a man, while a female servant looks on and a small dog begs at her feet. Is the dog merely a symbol of status—or does it allude to fidelity? The gesture of offering chocolate, too, may carry a double meaning. © Alkimia en Provence

Chocolate was first introduced in Spain as a drug. However, chocolate raised several religious and medical controversies. The doctors didn’t seem to agree on the virtues or vices of the exotic ingredient. In France, the letters of the Marquise de Sévigné to her daughter illustrate the back and forth on the subject.

Could a substance so indulgent, offering such pleasure, truly be beneficial to both body and soul? And could it be permitted during the Lenten fast? On these questions, even the Dominicans and Jesuits failed to agree.

Chocolate was believed to be not only restorative but also aphrodisiac—an idea playfully alluded to in the 1695 print shown above in our chocolate pots section, where a man and a woman share a cup of chocolate, a gesture laden with subtle sexual innuendo. As Louis Lémery wrote in 1702: “Chocolate arouses the ardor of Venus.”

Endorsed by the French Royalty

At the French court, the royals and aristocrats could drink chocolate alone for breakfast or as a snack. The sophistication of this delicacy made it an ideal offering for social calls, too. Philippe d’Orléans, regent from 1715 to 1723 until the majority of Louis XV, would invite guests to his morning chocolate. The affluent would have chocolate parties. The drink made its way to the public. The first Parisian shop for “drinking chocolate” opened in 1671 (a chocolate house). In 1705, any café could legally sell chocolate drinks or chocolate ice.

This conversation piece, painted in 1768, represents the illustrious family of the Duke of Penthièvre (the wealthiest French prince, grandson of Louis XIV and Madame de Montespan), who is on the left. In the center, his daughter-in-law—the Princess of Lamballe, who later became a close friend to Queen Marie-Antoinette—holds a chocolate cup, as do two other characters in this painting. © Château de Versailles, Dist. RMN / © Christophe Fouin

Louis XV was an avid lover of chocolate and some other earthly sensual pleasures, all good reasons for Madame de Pompadour and Madame du Barry to relish it as well. As written by Menon in 1755 in “Dinners of the Court or the Art of working with all sorts of foods for serving the best tables following the four seasons” [BnF, V.26995, volume IV, p.331) From Versailles Palace Website], Louis XV’s hot chocolate recipe was:

Place an equal number of bars of chocolate and cups of water in a cafetiere and boil on a low heat for a short while; when you are ready to serve, add one egg yolk for four cups and stir over a low heat without allowing to boil. It is better if prepared a day in advance. Those who drink it every day should leave a small amount as flavouring for those who prepare it the next day. Instead of an egg yolk one can add a beaten egg white after having removed the top layer of froth. Mix in a small amount of chocolate from the cafetiere then add to the cafetiere and finish as with the egg yolk.”

Similar to previous queens and ministers, Queen Marie-Antoinette had a person dedicated to preparing her chocolate drinks. Her chocolate-maker added, for instance, orange blossom or sweet almonds to the cocoa drink.

The Trembleuse, an Ideal Chocolate Cup in the 18th Century

Let’s take a closer look at cups, as the French in the 18th century put their distinctive spin on a design particularly well suited to hot chocolate: the trembleuse. The name comes from the French verb trembler, meaning “to tremble” or “to shake.” This type of cup was a lifesaver to prevent spills—especially noticeable (and embarrassing) when drinking chocolate.

However, it’s important to note that the trembleuse wasn’t used exclusively for chocolate. Conversely, people often enjoyed chocolate using other types of cups as well. Cups were either purchased individually or included in sets.

This is not a trembleuse, as Magritte could have introduced this cup: An early Meissen chocolate cup, saucer, and lid from around 1740-1760. With a naturalistic decor, a rosebud for the lid knob, and a branch for the cup handle. © Rosita Rapetti Gallery

Regarding the trembleuse, we saw with the mancerina how there was first an external device on the saucer of a chocolate cup (a raised rim in reticulated porcelain or silver) to hold the cup.

However, whether due to the fragility of porcelain cupholders, the discouragement of silver following the French sumptuary laws of 1689 and 1709, or simply boundless creativity, there was a shift from adding a separate stabilizing device to instead modifying the saucer itself.

An Imari trembleuse in the early 18th century: porcelain cup, lid, and saucer with a raised silver rim. 11.5 cm high. © Bils Ceramiques

Thus, what could be done to the porcelain saucer itself? Two options come to mind: a saucer could either be elevated to better cradle the cup or made deeper.

The Saint-Cloud porcelain manufactory around 1720-1750 (probably even late 17th-century) went for the former option, with an integrated inner rim crafted in porcelain—raised just a few millimeters above the surface of the saucer.

Two Saint-Cloud soft porcelain trembleuse cups and saucers, circa 1700-1750. Saucer diameter in both cases: 12.7 cm. Left: white and blue with godrons (© JM Béalu & Fils). Right: Chinese-style prunus branches in semi-relief (© Galerie Verrier).

The latter option refers to the trembleuse cup as we know it today—paired with a saucer featuring a central well several centimeters deep. At the Sèvres porcelain manufactory, this design was originally documented as a gobelet et soucoupe à gaine (tapered cup and socketed saucer). A prototype of this innovative drinking vessel—shaped like a tumbler, which is also known as a tasse à la reine (queen’s cup)—was created in 1752 by the Vincennes manufactory, before its incorporation into Sèvres in 1756. The distinctive deep saucer was added in 1759.

Louis XV’s famed mistresses, Madame de Pompadour and Madame du Barry, were among its earliest admirers. Later, Louis XVI ordered 50 of them. The design was soon imitated by manufacturers in Berlin and Derby during the 1770s, and by Castelli around 1790.

Two early Sèvres trembleuses with high-sleeved saucers. Top: Painted by Capelle, a model similar in shape to the original 1759 “gobelet et soucoupe à gaine” (© Galerie Arcanes). Bottom: A later model with a lid contemporary to Marie-Antoinette with the same motifs as a tasse litron dated 1777 held by Le Louvre. (© Antiquités VB).

Where to Serve Hot Chocolate: From the Cabaret Tray to the Cabaret Table

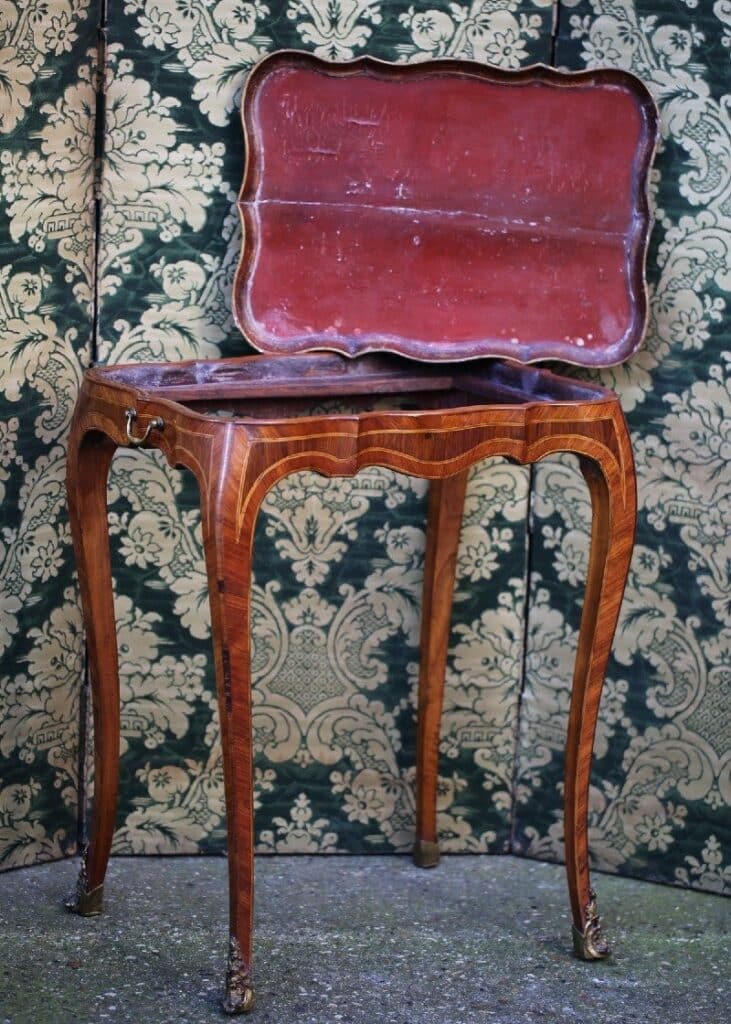

The chocolate (tea and coffee) sets we discussed earlier sometimes included a tray called a cabaret, as the restaurant or tavern that used such trays. The second edition of the French Academy dictionary in 1718 recorded a new meaning for cabaret: “A kind of small table or tray with raised edges, on which cups are placed for taking tea, coffee, etc.”

Close-up of the pastel on parchment by Jean-Etienne Liotard (1702-1789), The Chocolate Girl, circa 1744. Note the cabaret tray and the Kakiemon trembleuse cup. Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden (Public Domain).

The trays were first in lacquer imported from China or Japan and sold by the marchands merciers (To discover more about the marchands merciers, this profession essential to the development of French decorative arts in the 18th century, read this article about porcelain flowers). Then, they were produced in France in varnished wood to imitate lacquer (vernis martin) and later metal or porcelain.

The cabaret table saw widespread production in the 18th century. It coincided with the development of small tables starting during the Régence (seven years between Louis XIV and Louis XV). Such tables typically have cabriole legs. They could easily be moved around, for instance, set up for breakfast, then removed. The enthusiasm it inspired led to a proliferation of forms, making it one of the most elegant pieces of furniture of this period.

Louis-XV period cabaret table with a removable wood tray in red lacquer and side handles. Formerly in the Jacques Guerlain collection. © Olivier d’Ythurbide et Associé

You May Like

Chocolatière (Chocolate Pot) | Mancerina | Tasses (Tea, Coffee, and Chocolate Cups) | Cabaret Table